Children learn to communicate with others in a range of ways. Teachers and peers have an important role as communication partners for young children in early childhood and school settings. Research shows that the quantity and quality of teacher interactions is critical in supporting young children to learn. Children learn from what adults say and from how adults respond to their communicative efforts. Responsive interactions between adults and children can extend children’s language, as well as model effective communication in social situations. This research guide summarises key features of teacher responsiveness that support the development of children’s communication in educational settings, with a focus on children aged birth to 8 years.

How can teachers be responsive in their interactions with young children?

There are some key things that teachers can do to be responsive communication partners for the children in their care:

- Start with the child

- Create a rich communication environment

- Slow down and take your time

- View everyday situations as opportunities to communicate

- Use specific language and communication strategies

- Involve families and communities

- Document and record progress

Start with the child

It is important to view the child as an active communicator who is capable of sharing meaning. Even the youngest infants’ attempts at communicating and taking turns via their cries, coos and eye gaze can be recognised if adults pause to watch, wait and listen. Observe children’s interests and dispositions, as these provide information as to what they might be motivated to communicate about. Ask families about people, places, objects or home experiences important to the child so that you can build meaningful conversations around what is familiar and significant.

It is also helpful to notice how the child responds to questions or instructions during everyday situations and how much they seem to understand. Tune into the range of communicative modes used by children to express themselves throughout the day – for example, do they primarily use noises, words and sentences or rely on facial expressions, body language and gestures?

Create a rich communication environment

Take time to plan your environment to allow time, space and materials for supporting rich communicative interactions with children. Provide open spaces for larger group interactions as well as creating smaller areas for more intimate conversations, particularly for children who find it difficult to listen or sustain their attentional focus. Consider the amount of background noise in the environment, particularly for children who find it difficult to concentrate and listen during conversations.

Strategically position visuals such as photos, illustrations and print in the environment to support children’s comprehension. Facial expressions, body language and gestures are also visual supports that help to reinforce the meaning of what adults and peers are communicating verbally. Display words or symbols that represent the cultures of your children so that all the home languages are visible and reflected inside and outside of your classroom or centre.

Ensure there is a rich variety of activities and equipment available in the environment to stimulate children’s motivation to share information, solve problems and develop relationships. For example, natural, open-ended, unstructured materials including wood, stones, shells and feathers can promote communication about touch and texture, while blocks and manipulatives encourage problem-solving and description, and dramatic role-play resources can inspire and extend peer play and conversations related to social roles and situations.

Slow down and take your time

It is easy to suggest slowing down and making time for interactions with children throughout the day, but of course this can sometimes be a real challenge when things get busy! The key is to think ahead so that you can identify times when you can intentionally prioritise interactions with children, either alone or in small groups of 3 to 4 children. Allow time to observe and listen to children as they interact with you or with their peers. This allows you to tune into how and why they communicate with others, as well as to document specific details and examples as part of ongoing assessment around children’s communicative competencies. Unhurried interactions allow children to take the lead and give teachers time to pause, watch, wait, listen and then respond to the child’s initiations or interests. Expect conversations to be a two-way process. Invite children to engage with you in any way in which they are able to respond and take a turn, not only through words but also through gestures like pointing, body language or other actions.

View everyday situations as opportunities to communicate

Many opportunities exist for responsive interactions with children to be woven informally and naturally into many situations throughout the day. Care moments and routines, play activities, and songs, stories and rhymes are examples of informal contexts that support rich communicative interactions.

Care moments and routines

Care moments include feeding, bathing, dressing, nap time and getting changed, and are ideal opportunities for one-on-one communication with infants and toddlers in early childhood settings. Daily greetings and farewells are also good times to practice social language and interactions for children of all ages – this can be as simple as saying ‘good morning’ with eye-contact. You can add language to actions as they happen by sharing what you and the child are doing together during everyday care moments and routines. For example, you might say ‘Let’s put our jackets on’, ‘Arms in…’ or ‘Up goes the zip!’ while getting changed to go outside.

Play activities

Communication is inherent to all kinds of play including exploratory, constructive and pretend play with others. Children communicate during play through listening as well as using their bodies in space. They also use actions, gestures, noises, facial expression and words. Pretend play extends children’s language from the ‘here and now’ to imaginary situations using decontextualised language (discussing people, places and things not immediately present), which is fundamental for the development of children’s abstract thinking and learning.

Music, stories and rhymes

Music, songs, stories and rhymes are important tools for supporting children’s communication and literacy development. Ask families about songs, stories and rhymes and incorporate them into your day wherever possible in order to represent the cultures of all the children in your centre or class. Songs, poems, rhymes and finger plays can also enhance children’s listening and awareness of sounds and words through melody, rhythm and actions. Play around with sounds and rhymes in words through songs, poems, chants and games (such as ‘I spy with my little eye’). Listening and playing with sounds supports children’s phonological awareness, an important part of being able to develop speech, language and literacy.

Use specific language and interaction strategies

Teacher strategies for providing responsive interactions will vary depending on the age of the child, but research shows that for all children, warm teacher interactions that follow and extend children’s interest and attempts to communicate are what matter most. Eye-contact, touch and gestures are important for the development of joint attention and comprehension, particularly for infants and toddlers. Watch, wait and listen for children’s cues before you respond. Copying a child’s actions during play is also a way to affirm what young children are doing. This can be further extended into taking turns together. Invite children to take a turn, and then wait, allowing extra time or gentle prompts (such as ‘Your turn?’) if needed.

Another strategy for building children’s knowledge of language is using rich and varied vocabulary with words and sounds that make learning fun as you engage with children in play and learning contexts (for example, saying ‘We’re squashing it and squishing it!’ while playing with playdough). It is also important to use accurate language to build children’s understanding of specific concepts relating to content knowledge. For example, outdoor play or science activities provide many opportunities to talk about nature, size, shape, textures, quantity and temperature as well as to use specialised language related to topics (such as explaining the terms ‘larva’ and ‘cocoon’ when learning about butterflies). Validate what children say and expand on it using new words and phrases to expand and extend upon their ideas, pitching your language just ahead of where the child is at, for example:

Child: Look at my tiger!

Adult: Your tiger looks fierce! You’ve drawn a long tail too.

Offering children choices using simple language and/or objects and gestures can help provide scaffolding in how to respond for children with little verbal language – for example, you can ask ‘Do you want the green or yellow paper?’ while also showing or pointing to the two colours of paper. In general, it is better to use more comments and fewer questions when talking informally with children, as too many questions can make children feel as if they are being tested. During a drawing activity, for example, instead of asking ‘What are you drawing?’, ‘What colour is that sun?’ or ‘Where will the house go?’, you could use comments such as ‘I like your house’ or ‘That’s a pointy green roof!’ along with occasional open questions like ‘I wonder who lives upstairs?’

Allow children to initiate topics of conversation rather than the typical ‘teacher initiation-child response-teacher feedback’ cycle where teachers lead the interaction. Finally, encourage older children to develop verbal reasoning by asking ‘what do you think is going to happen next’, or ‘what would happen if…’. Use language to create imaginary scenarios that extend children’s language and thinking beyond the ‘here and now’.

Involve families and communities

It is important to recognise the expertise of families in knowing about how their children communicate, including strengths and challenges. Find out about the language(s) used at home[SM10] , including different dialects, and keep a record of some key words or phrases that can be used in your centre or classroom. You can also ask about a child’s interests or any exciting experiences or outings as starting points for communicative interactions or as topics for extending play and learning. Ensure that you ask parents or caregivers if you have any concerns about aspects of a child’s general health and development that might be impacting on their communication, including hearing and listening.

Document and record progress

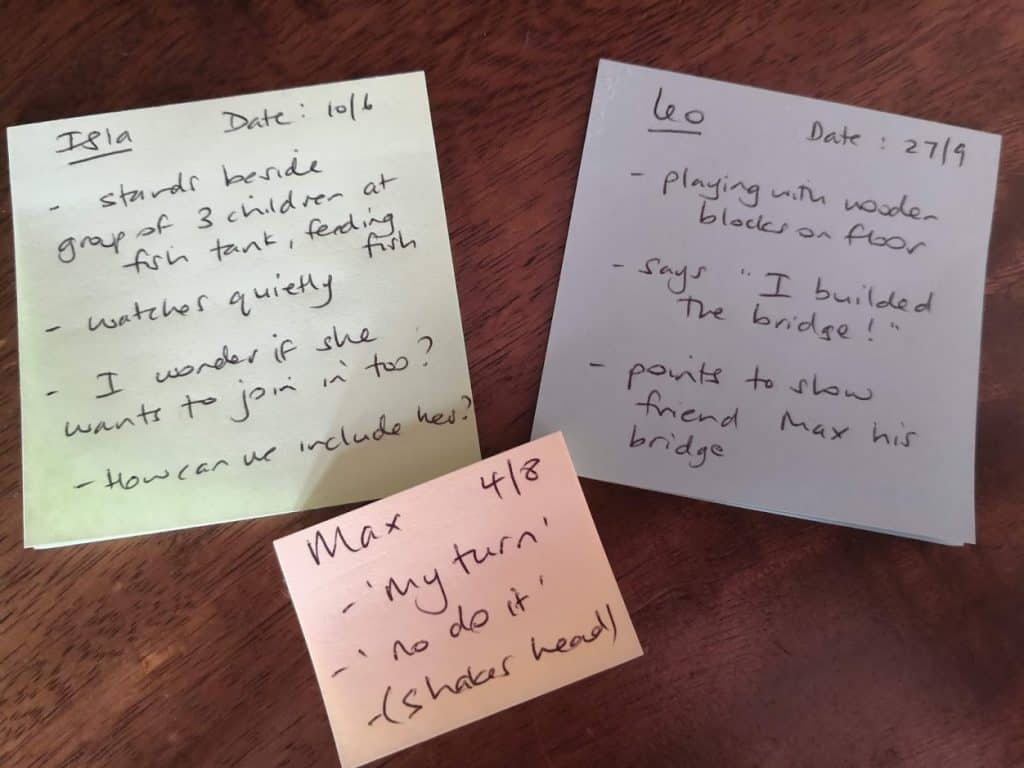

Documenting each child’s communicative strengths and challenges at regular points will allow you to monitor progress and development over time. Informal assessment of communication can include the observation and recording of samples of children’s language, including descriptions of how they communicate using their gestures, actions and words, and any communication breakdowns or challenges that arise. Post-it notes can be handy to quickly record your thoughts or observations on the fly (see Image 1) and then written up later (see Image 2).

Video-recording short clips of yourself or colleagues can also be an excellent tool for feedback and reflection. Consider the quantity and quality of interactions – for example, how and why does this child communicate? Are our interactions balanced or do adults do most of the talking? Am I using comments or asking too many questions? Finally, think about how your observations of the child relate to curriculum goals as well as the child and/or family’s aspirations as this can help to evaluate progress and prioritise communication goals for future learning.

Recommended Reading

Dalli, C., Buchanan, E., White, E. J., Rockel, J., & Duhn, I. (2011). Quality early childhood education for under-two-year-olds: What should it look like? A literature review. Report to the Ministry of Education. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Education.

McLachlan, C. (2018). Te Whāriki revisited: How approaches to assessment can make valued learning visible. He Kupu, 5(3), 45-56.

Podmore, V. N., Hedges, H., Keegan, P. J., & Harvey, N. (2016). Teachers voyaging in plurilingual seas: Young children learning through more than one language. Wellington, New Zealand: NZCER Press.

Test, J. E., Cunningham, D. D., & Lee, A. C. (2010). Talking with young children: How teachers encourage learning. Dimensions of Early Childhood, 38(3), 3.

Weitzman, E., Girolametto, L., & Greenberg, J. (2006). Adult responsiveness as a critical intervention mechanism for emergent literacy: Strategies for preschool educators. In L. M. Justice (Ed.), Clinical approaches to emergent literacy intervention (pp. 75-120). San Diego, CA: Plural.