Close and caring ongoing relationships support all aspects of infants’ and toddlers’ development and learning. These early relationships are primarily with other people but also with places and things. Experiences of responsive, attuned caregiving in the first years of life facilitate emotional and cognitive wellbeing, so a curriculum for infants and toddlers must have strong relational connections at its centre. Infants and toddlers need adults who are willing and able to engage with them in attuned interactions and relationships that are characterised by intimacy, sensitive responsiveness and focused presence.

Infants and toddlers need constant and affectionate company provided by an intimate relationship with their caregivers, and experiences of positive relationships in infancy have far-reaching consequences. The sense of safety provided by a warm and secure relationship promotes children’s investigation of the world and enables them to gradually establish multiple relationships with others. First relationships with a caregiver provide a model for relationships with subsequent teachers and also set the foundations for adjustment, development and learning across a child’s education. Strong, attuned relationships support children’s resilience and security. Through relationships, young children learn how to be empathetic to others’ feelings, to grow and manage their will, to stand up for their own needs and rights and ask for them to be met, to negotiate, manage and express their feelings, and to develop conflict resolution skills.

Research has found that negative early childhood experiences characterised by unresponsive, inconsistent and unstable relationships within stressful environments have a negative effect on brain development. Low quality care and an inadequate relationship with an adult are sources of stress, especially when infants and toddlers have no control over events and no access to or support from a soothing caregiver. Stress is toxic and has a negative impact on brain development, the immune system, emotional wellbeing and cognitive skills, both immediately and later in life. Some areas of the brain that are dependent on emotionally attuned relationships do not activate, and these ‘holes’ in the architecture of the brain can remain across a child’s lifetime. Without the experience of emotionally attuned relationships in early life, infants and toddlers show an impaired ability to regulate their emotions, and without the opportunity to learn socially acceptable behaviours from caring and responsive interactions, they internalise negative patterns of interaction. These effects have a detrimental effect on future relationships.

Pedagogical strategies that strengthen the quality of relationships

Infants form relationships more readily with teachers who show an interest in them and match their own behaviours to the child’s. Infants also form strong relationships with teachers who have a positive outlook, a belief in their ability to form relationships with infants, a gentle and responsive style of interaction, and strong non-verbal communication skills. It is important to bear in mind that there can be contextual constraints that prevent the development of positive relationships between infants and caregivers, including high ratios of children to adults and larger groups of children. Teachers are found to provide more sensitive, frequent and positive care, to act more responsively, and to be increasingly nurturing and warm when they are responsible for fewer children. Low-stress environments that support healthy brain development are also related to the structural qualities of small group sizes and low ratios of children to adults, as well as the presence of supportive relationships.

- Calm, unhurried environments

Research shows that the quality of infant and toddler environments has a marked impact on children’s development and learning. Meaningful and intimate relationships develop in environments that are unrushed, peaceful and tranquil. Environments should be amiable and calm, with a flexible and relaxed pace or rhythm to the day, so that interactions and relationships can be given the time, focus and support required. This also enables teachers to give infants and toddlers time and space (without interruption) to play and lead their own learning. Calm environments enable teachers to reflect on the quality of interactions and on relationship development, so it is important to monitor the environment for noise level and the balance of opportunities for quiet rest as well as energetic play. Young infants may benefit from safe spaces in which to lie on their backs without fear of toddlers stumbling over them. Ongoing observation and reflection will ensure that environments continue to support children to feel content and curious.

- Consistency over time

Continuity in relationships and consistent caregiving by one or a very small number of teachers enable caregivers to form warm relationships with infants and toddlers in which they can sensitively respond to their changing needs and preferences, and celebrate their achievements and learning. Many settings advocate primary caregiving as a strategy for achieving attentive relationships. Continuity in the caregiver-child relationship builds up more secure and trusting relationships between teachers, children and parents, and also is related to resilience in children. Building an attentive relationship over time will provide many opportunities to observe the infant or toddler across a variety of experiences, enabling teachers to learn what excites, amuses, upsets and frustrates the child and become increasingly sensitive to the child as an individual. It will also allow teachers to come to know what the child knows, understands and is interested in. This is especially important during the infant and toddler years because children’s communication requires more careful observation and interpretation. Teachers should aim to ensure ongoing, consistent and stable relationships and attachments. This means considering how decisions about the programme, room changes or teachers’ schedules or leave will affect relationships, and seeking solutions that support rather than undermine existing relationships. Consistency can also be promoted through daily routines that build a sense of security and familiarity, and by ensuring that colleagues have similar approaches and pedagogies to the care and education of infants and toddlers.

- Listening

Infants and toddlers communicate in many complex and subtle ways. With each child teachers will need to develop a ‘watchful attentiveness’ to their vocal and body language, watching all their signals and listening for their cues. Infants in particular use all the resources they have available to communicate – nuances of sound, volume and pitch, as well as dramatic whole body movements such as arching the back or waving their arms and legs about. Listening involves all the senses, not just listening but also looking with attention to pick up on the cues that infants and toddlers use to express pleasure, contentment, sadness, anxiety, trust, wonder and surprise. In particular, listening involves a lot of waiting , giving infants and toddlers time, space, and support to express themselves, as well as giving teachers the opportunity to get to know and understand their behaviours and cues.

- Presence

Attuned interactions with infants and toddlers depend on teachers’ physical and emotional presence, and their ability to orient themselves towards the child’s experience rather than focusing on strategies, techniques or rosters. Presence is an important component of a caring relationship — it makes infants and toddlers feel safe and nurtured and has a significant impact on their emotional well-being. Teachers need to be physically available to children, making space or access for children to be near them or on their lap, but also ‘being there’ requires them to actively make eye contact, display appropriate body language, and respond to infants’ and toddlers’ cues. It involves being engrossed in the infant or toddler, as well as being receptive to them, paying close and full attention to them in the moment. This attentiveness means that teachers are still and quiet, actively present but not actively doing. Teachers need to trust in the child and in themselves that this attentive presence, this ‘doing by not doing’, is part of sound pedagogical practice, and allow the time and space just for being present, reflecting, and interpreting what they are learning about the child by being present.

Interactions that build relationships

In interactions with infants and toddlers teachers need to show sensitivity, presence and an active involvement in the child’s experiences and actions. Attuned relationships with infants and toddlers consist of specific types of responsive and reciprocal interactions that are individualised, sensitive and timely in response to infants’ and toddlers’ verbal and non-verbal cues. Generally these are one-to-one interactions which facilitate the effective reading of infant and toddler cues and that allow for particular kinds of exchanges including episodes of joint attention. In particular, imitation, joint attention (or inter-subjectivity) and empathetic understanding are three skills that are developed in infancy which serve as foundations for social development and enhance the learning of the infant or toddler. Repeated experiences of positive interactions help infants and toddlers develop the ability to trust others. The nature of teachers’ interactions with infants and toddlers has the potential to improve or limit learning.

- Responsiveness

Sensitive and responsive caregiving supports infants and toddlers with emotional regulation and promotes the development of neural pathways necessary for learning. Being responsive to the infant or toddler’s communications through listening and being present enables teachers to move forward in their understanding of them and, equally, enables the infant or toddler to develop their understanding of the teacher. When a teacher responds to a distressed infant, the child will begin to generalise the teacher’s presence as providing a sense of wellbeing and security. Even the youngest of infants can encode implicit memories before they develop conscious attention of the experience.

- Reciprocity

A teacher’s relationship with an infant or toddler should be two-way and reciprocal, in that each seeks out the other, learns from the other, and adjusts in response to the other’s behaviour, development and change. In reciprocal relationships, teacher and infant are both involved in maintaining and developing the relationship but will perform different roles and behaviours. Often, the infant or toddler will take the lead, and the teacher’s role is to be observant, reflective and responsive. Developing reciprocity in interactions means that it is important to stop, look and listen for the infant’s or toddler’s response. Learning and teaching become reciprocal when teachers learn from the children as they learn from teachers. Reciprocal dialogues are important, and are developed at an early age often through eye contact and the use of gaze, or mutual eye-to-eye contact which lasts more than a second. It is important to respond to the ‘look’ initiations of infants. Teachers can also enable reciprocity in their relationships with infants and toddlers when they tell infants and toddlers what they are going to do before doing it, ask infants and toddlers for their co-operation, wait for them to process the request, and offer choices.

- Imitation

Reciprocal imitation is an important interactional and intentional strategy which encourages infants and teachers to delight in interactions with each other. Infants in particular are fascinated by seeing others respond to the rhythm, intensity and style of their movements and vocalisations through imitation, or in some other way matching their response to the child’s or building on their communication. Infants enjoy the familiarity and sense of complicity associated with seeing their own behaviour returned to them.

- Joint attention / inter-subjectivity

Inter-subjectivity is a special quality of interaction and relationships which involves connectivity or communion between two people who attend to each other’s cues about their emotions, thoughts and interests. Joint attention occurs when the teacher and the infant or toddler pay joint attention to, and perhaps jointly act upon, some external object, activity or idea. Infants as young as eight or nine months are capable of brief moments of joint attention, and episodes of joint attention become much more frequent by 15 to 18 months of age. Infants and toddlers have strong inclination, desire and ability to engage adults and others in satisfying communication and joint involvement, and will often initiate these interactions. Engagement in a shared activity or focus is enjoyable, provides a sense of delight and emotional connection, and supports the release of hormones in infants for the development of brain cells and neural pathways. At the same time, as an inter-subjective partner for the infant or toddler, teachers can optimise opportunities for learning and development, for example, by providing language and a frame of meaning for the child, appropriate to his or her understanding and the shared context. Research links joint attention to the development of a range of cognitive and social skills, including increased abilities in language and communication. This means that it is not the activity or objects per se that constitute valuable curriculum experiences, but the extent of the adult’s collaboration with the infant or toddler in regarding those objects and activities.

Relationships with families

Relationships between teachers and parents influences an infant or toddler’s view of their teachers, as they rely on their parents and family members as important referees. They are more likely to accept and build a relationship with a new caregiver when they sense that he or she meets their parents’ approval, so building relationships with families is an important part of the transition and settling process for a new child. In addition, because infants’ and toddlers’ development takes place in varied family, cultural and linguistic contexts, relationships with families help teachers to understand the lives that children and parents lead. Developing a solid relationship base requires getting to know the child’s context and family. In this way teachers can develop sensitivity and understanding towards diverse values, beliefs, expectations and aspirations, and draw on the expertise of the parents who know their own child and his or her communications and routines very well.

Developing warm, trusting relationships and open, pleasant and relaxed communication with families enables teachers to work collaboratively with families to provide the best care and learning experiences for children. A very important part of the teacher’s role is to value and support relationships between parents and children. Teachers can use their relationships with parents to promote the pedagogical value of parents enjoying their children’s company and spending time in reciprocal interactions with them from a very young age. There are many ways in which teachers can facilitate ongoing information-sharing and collaboration with families through home and centre visits, and daily written and verbal communications and dialogue. It might be useful to discuss relationship goals and how the child’s relationships are developing to see how families might be able to contribute to this. Look for ways to strengthen parents’ relationships with their child as well as their relationship with teachers and the early childhood setting.

References

Dalli, C., White, E. J., Rockel, J., Duhn, I., with Buchanan, E., Davidson, S., Ganly, S., Kus, L. & Wang, B. (2011). Quality early childhood education for under-two-year-olds: What should it look like? A literature review. Wellington, NZ: Ministry of Education.

Dalli, C., Rockel, J., Duhn, I., & Craw, J. with Doyle, K. (2011). What’s special about teaching and learning in the first years? Investigating the “what, hows and whys” of relational pedagogy with infants and toddlers. Summary report. Teaching and Learning Research Initiative. Retrieved from http://www.tlri.org.nz/sites/default/files/projects/9267_summaryreport.pdf

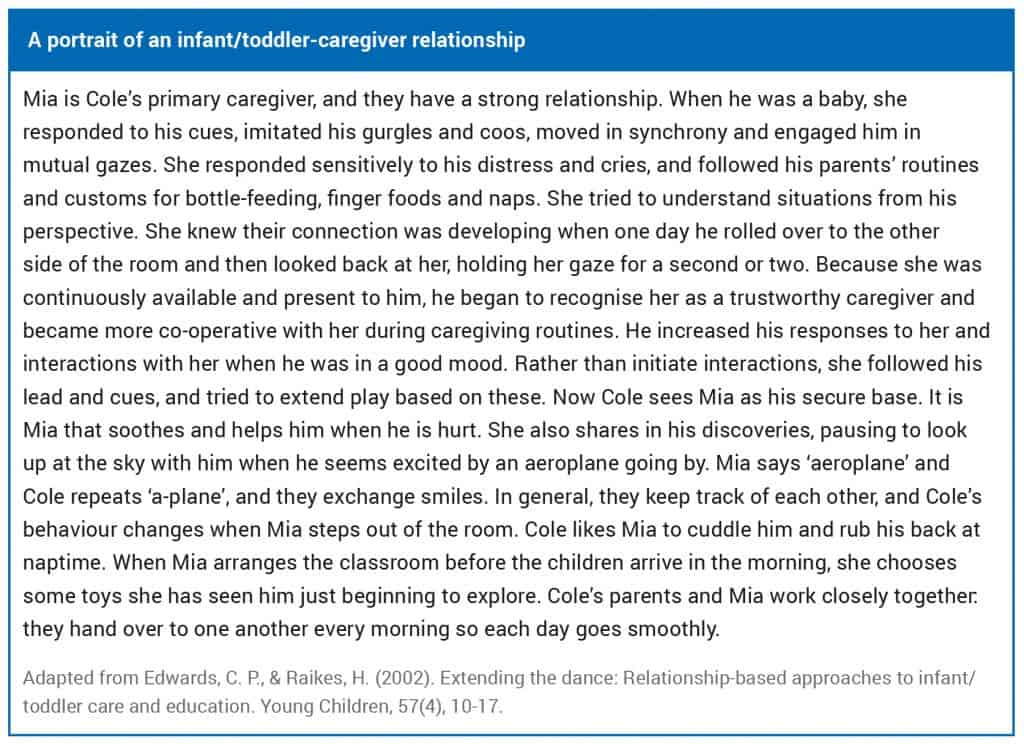

Edwards, C. P. & Raikes, H. (2002). Extending the dance: Relationship-based approaches to infant/toddler care and education. Young Children, 57(4), 10-17.

Goodfellow, J. (2008). Presence as a dimension of early childhood professional practice. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 33(1), 17-22.

Parker-Rees, R. (2007). Liking to be liked: Imitation, familiarity and pedagogy in the first years of life. Early Years, 27(1), 3-17. doi: 10.1080/09575140601135072

By Dr Vicki Hargraves