This section provides a brief overview of the theories of learning to read and write. More detailed information on reading and writing can be found here.

In this section

Understanding reading

The ultimate aim of reading is to comprehend a text. Reading comprehension success requires mastering both oral language and its printed form.

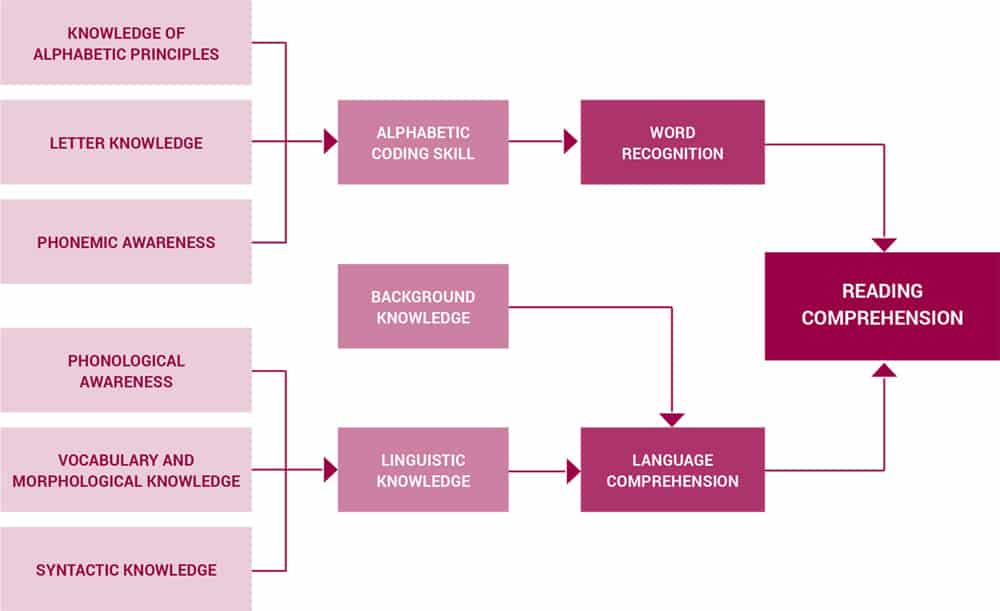

The Cognitive Foundations Framework provides a useful model for understanding the building blocks that need to be developed (and taught) to ensure success in reading.

- Reading comprehension is being able to gain literal and inferred meaning from reading a printed text.

- Language Comprehension is the ability to make meaning from spoken language.

- Background knowledge refers both to what one knows about the topic, that is the content being written about or discussed, as well as aspects of how texts work, including, for example, elements of narrative such as plot, setting, characters, and themes. Inferencing is the ability to use language clues to go beyond what the words say on the surface to consider the deeper meaning of the text.

- Linguistic knowledge incorporates the form, sounds and meaning of language at both the word level and at the sentence level.

- Phonological knowledge involves recognising the speech sounds of a language. Phonology of language is the word itself, as well as the syllables and the phonemes, which are the smallest units of sound that make up a word.

- Vocabulary or Semantic knowledge is the meaning of individual words and words within sentences and morphological knowledge is the ability to recognise morphemes (the smallest meaningful lexical item in a language e.g. trans or ism) in words.

- Syntactic knowledge is the way words work together in a sentence and is governed by the specific rules of a language. For example, English is based on subject-verb construction.

- Word recognition (or decoding) is the understanding that in English both systematic and unsystematic (idiosyncratic/exceptional) relationships exist between written and spoken forms of words.

- Alphabetic coding skill is the ability to use the alphabetic principle to read and spell words.

- The alphabetic principle refers to knowing that a systematic relationship exists between the phonemes (smallest unit of sound, e.g. c-a-t in cat or ch-a-t in chat) of spoken words and the graphemes of print (a written symbol that represents a phoneme).

- Letter knowledge isthe ability to recognise and manipulate the units (letters) of the writing system.

- Phonemic awareness is the conscious knowledge that words are built from a discrete set of abstract units, or phonemes, coupled with the conscious ability to manipulate these units.

Understanding writing

Writing involves the coordination of many elements, including: basic skills such as letter formation, spelling, and punctuation use; knowledge of one’s purpose for writing; knowledge of the conventions of genre, sentence structure, and text organisation; as well as the coordination of the writing processes, which include planning, re-reading, evaluating, and revising.

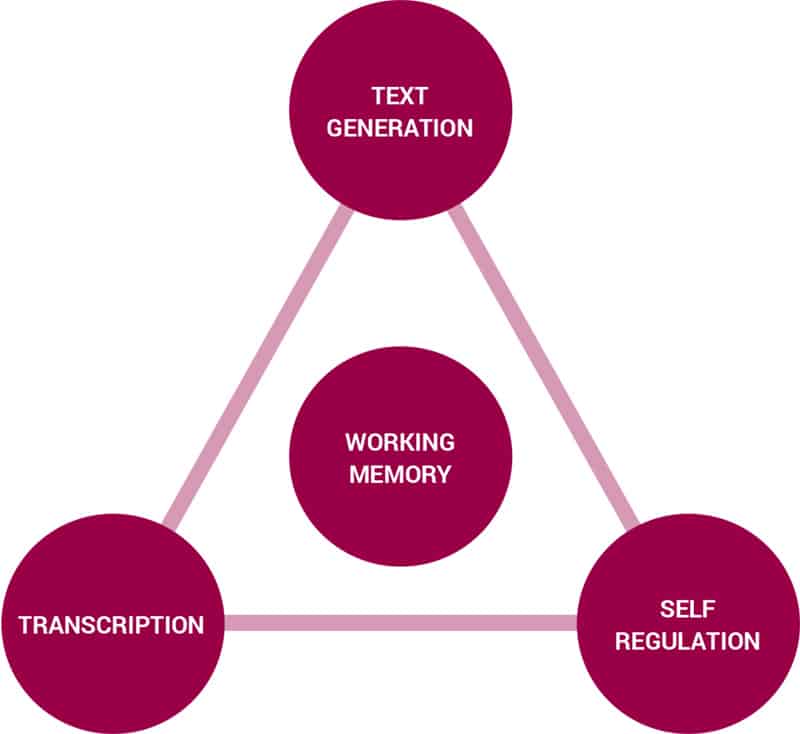

The Simple View of Writing (sometimes called the ‘Not So Simple’ View of Writing to highlight how much more complex it is than reading) demonstrates that writing composition depends on three areas of skills, which in turn are all reliant on working memory.

- Transcription skills are those skills required to get words down on a page – spelling and handwriting.

- Text generation, which sometimesis referred to as translation, is the expression of thoughts in writing, and requires vocabulary knowledge and sentence-generation skills, as well as understandings of such concepts as genre, voice, and purpose.

- Executive function or self-regulation refers to the ability to monitor and direct the writing or composition process. Skilled writing involves the coordination of the writing task, goals, and ideas with the processes of planning, re-reading, evaluating, and revising.

- Working memory is where information – both new and information retrieved from long term memory for use – is processed. It is defined by its limited capacity, both respect to how much information can be processed at any one time and how long information is stored. In the simple view of writing, working memory also encompasses the knowledge one brings to writing.

Videos to watch

Please note, when the video plays, you can use the controls at the bottom of the player to expand the video to full screen.

The components that make up early writing instruction

Dr Helen Walls explains the Simple View of Writing and what it means for early writing instruction in primary schools.

The reading-writing link

Dr Helen Walls discusses the connection between reading and writing and in particular the importance of phonemic awareness and handwriting.

Examples of undertaking a school-wide literacy improvement journey

Hokowhitu School

Lin Dixon, Principal, and Helen Griffin, Senior Leadership Team Member, discuss how and why they changed their approach and the impact that it has had on their students, teachers, and parents.

Nayland School

Literacy Leader Maree McMahon discusses what spurred Nayland School to relook at literacy teaching, the changes they have made, how they have approached these changes, and the impact they are having.

Tawhero School

Principal Karleen Marshall and teacher Stephanie Robinson discuss how employing a systematic approach to the teaching of literacy has led to substantial improvements in reading and writing and has also had significant impacts on teachers.