All educational assessments should have a clear purpose, provide information that is trustworthy, dependable and appropriate, and have beneficial outcomes for all learners.

Validity, reliability and fairness are the three pillars of sound educational assessment and are interconnected in ways that demand careful attention be given to each. They are universally important qualities that apply to:

- informal and formal assessments

- assessments for learning and assessments of learning

- assessment information gathered in early childhood education (ECE) settings, kura and schools

- classroom/ECE-based assessments and large-scale tests and examinations

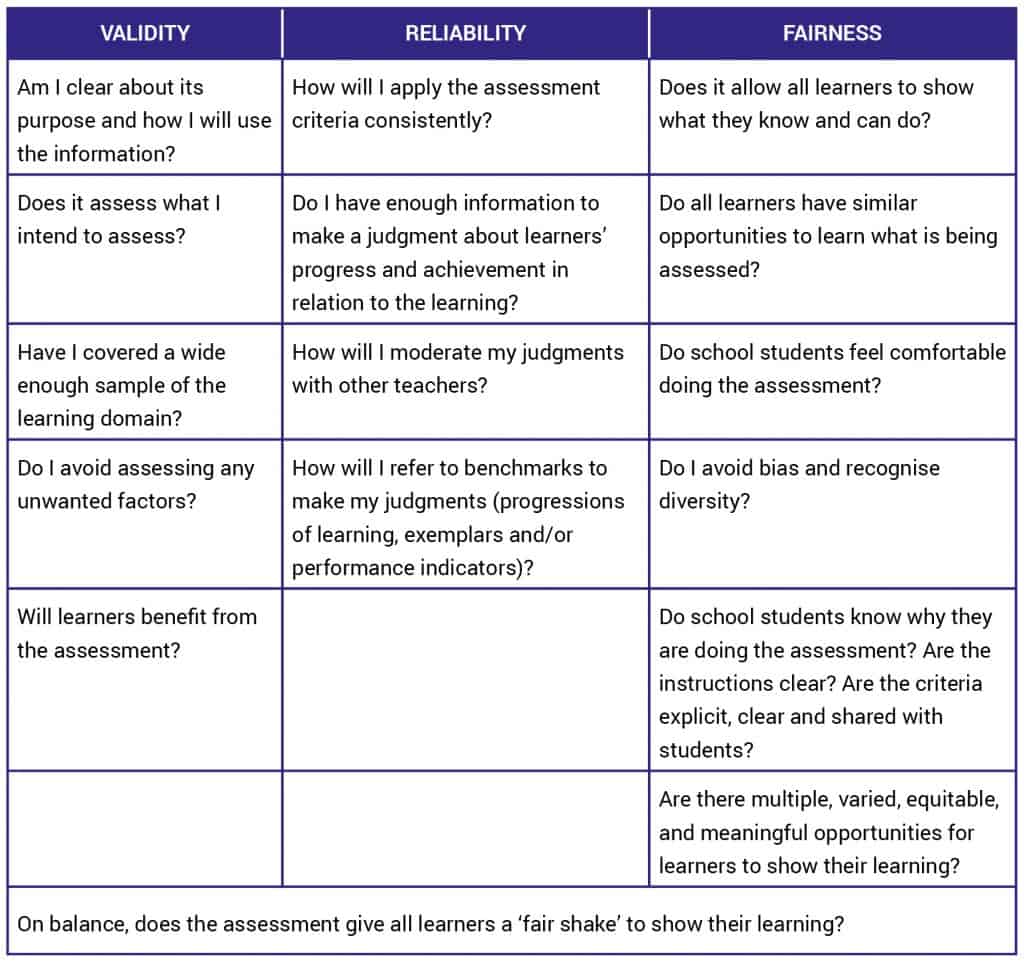

Teachers can ensure assessment is valid, reliable and fair by asking these questions:

Assessment in ECE, kura and school settings

The national curricula (Te Whāriki, Te Marautanga o Aotearoa, and The New Zealand Curriculum) identify valued learning outcomes and achievement objectives consistent with their respective mission statements and principles. Information about learners’ progress and achievement can be gathered in a variety of informal and formal ways. Examples include:

- teacher observations

- annotated photographs, written narratives or learning stories

- teacher-developed assessment activities or tests and exams

- published tests, such as Progressive Achievement Tests

- external examinations for qualifications, such as NCEA

- online resources, such as e-asTTle

Teachers in ECE settings do not use test-based assessments. Here, assessment is more holistic and based on noticing, recognising and responding to a child’s interests. A child’s learning is documented in learning stories in relation to learning outcomes, and based on their interests, strengths and dispositions.

Evaluating the quality of assessment – an argument-based approach

Statistical evidence of validity and reliability is usually reported for published tests and large-scale tests and examinations. However, for assessments undertaken by teachers in ECE, kura and schools an argument-based approach is more appropriate for evaluating the validity, reliability and fairness of an assessment or programme of assessment. Teachers can ensure their assessments are as valid, reliable, and fair as possible by considering both the evidence that supports their claims and the impact of any factors that may threaten or weaken them.

Validity

Validity is concerned with gathering assessment information and ensuring the assessment is fit for purpose and does no harm. Validity has traditionally referred to an assessment instrument itself. More recently though, and of more relevance for teachers in ECE settings, kura and schools, validity is better understood as the quality of the interpretations and decisions that are made on the basis of assessment results or observations. Teachers can do this by using a validity argument. In evaluating the validity of an assessment, it is important to consider both the evidence that supports claims for validity and the impact of any factors that may weaken claims for validity. There are different types of validity.

- Construct validity: Does the assessment cover the learning intended or capture the learning noticed?

Construct validity is at the heart of a validity argument. Constructs are the specific attributes or traits that you want to assess, such as reasoning skills or reading comprehension. For example, a construct in a maths assessment may be problem solving. Constructs are also specific learning, interests and dispositions you are seeking to capture. For example, an ECE assessment about making connections between people and places could be captured in a learning story about a visit to a local marae. Teachers need to have a good understanding of the construct and traits of the learning activity, and how they can be demonstrated or captured through assessment.

Construct validity can be strengthened by including a reasonable coverage of the important traits of the main construct in an assessment and excluding other ‘confounding’ factors that are unrelated to the construct. For example, when the reading demands of the maths problems in a maths assessment become an obstacle to students understanding the problem, this is a confounding factor. The information from the maths assessment will be less valid for less able readers, and therefore less of a true reflection of their maths ability.

- Content validity: Does the assessment include a reasonable coverage of the learning domain to be assessed?

A domain is an area of learning, such as learning outcomes of Te Whāriki or maths achievement objectives in The New Zealand Curriculum (NZC). A single assessment cannot cover the whole domain you are interested in assessing, so it is important that the assessment includes a fair sample of the domain or captures sufficient evidence so that you can be confident about any inferences you make about learners’ abilities in that domain. This means that teachers need to be able to match the scope and nature of the learning domain to assessment tasks and learning outcomes. Sometimes, this might require teachers to write an assessment plan that details the skills, knowledge, dispositions and contexts to be assessed/captured within an assessment or across a programme of assessment. Content validity can be improved by matching learning opportunities to learning outcomes, by matching assessment tasks to learning intentions, and by having discussions with colleagues.

- Consequential validity: Is the assessment information used for the purpose for which it is gathered and in ways that are beneficial for learners?

This refers to the consequences of the assessment, and the uses to which it is put. Consequential validity will be high when the assessment information is used to support and promote individuals’ learning. However, consequential validity will be low when the assessment information is used for a purpose for which it was not intended. For example, if the assessment information collected to inform individuals’ learning in the ECE, kura or school settings is also used to judge a teacher’s performance, then the assessment information becomes ‘high stakes’ for the teacher, and assessment may become distorted.

In evaluating the consequential validity of an assessment, teachers should consider the potential impact the assessment will have on learners, on themselves, and on others who will use the information. Teachers particularly need to question the validity of assessment when there is evidence that the information intended to inform teaching and learning is used in ways that may be detrimental or harmful to learners, such as when informal data gathered in class is used for high stakes purposes.

Reliability

Reliability is concerned with the accuracy and consistency of the information collected from an assessment and the dependability of the judgments that teachers make about learners’ progress and achievement. When assessment information is accurate and consistent, we can be confident that it is a reliable representation of what is being assessed. When there is sufficient moderated assessment information, we can be confident that teachers make dependable judgments and decisions. Teachers should aim to develop assessment procedures and tasks that are as reliable as possible. The level of reliability that is acceptable for an assessment or judgment also depends on the purpose of the assessment and how the information is to be used.

Reliability may be considered as different forms of consistency:

- Teacher consistency: Does a teacher apply the assessment criteria in the same way for all learners?

Teacher consistency will be strengthened if the teacher can apply assessment criteria consistently for different learners in an unbiased way.

- Consistency across teachers: Would the assessment information collected be similar if someone else applied the same criteria to observations of individual learners or marked the assessment?

Consistency across teachers gives an indication of how much different teachers agree when they judge the same assessment using the same criteria. Consistency across teachers will be strengthened if teachers have a shared or common understanding of the criteria and learning outcomes, and they apply them in the same way.

- Consistency across assessment information: Would teachers get the same information if they used different assessments to assess the same learning or if they observed learners in different contexts?

When the information from two different sets of assessment that assess the same construct is similar, we have reasonable evidence to claim that the assessment has consistency across the information collected.

- Consistency across time: Would teachers get the same assessment information if learners were assessed at a different time with the same or equivalent assessment?

When the information from the assessment that is used at different points in time is similar, we have reasonable evidence to claim that the assessment information collected has consistency across time.

Dependable judgments

Teachers are far more likely to make dependable and meaningful judgments about learners’ progress and achievement when they collect and consider assessment information from multiple sources, engage in moderation activities, and/or use benchmarks to judge learners’ performances or learning. This is particularly important when teachers use the information to make decisions about teaching and learning, and when reporting back to learners and their parents or whānau.

Teachers can ensure their judgments are as dependable as possible by considering the following:

- Sufficient information: Does the teacher have enough information to make a dependable judgment about learners’ progress and achievement?

When teachers gather multiple sources of evidence from assessments with strong reliability, it is more likely that dependable judgments and decisions will be made. Using three different sources of evidence (triangulation) may provide sufficient information for making this judgment. These might include observations of learning, products that learners create (including artefacts and assessment results) and learning conversations with the learners.

- Moderation: Do teachers make similar judgments based on the same assessment information?

It is also important to compare how other teachers apply criteria to the same assessment task, to discuss your interpretations of the criteria and to adjust them so that they converge. This will help teachers develop a shared understanding of the criteria as well as promoting collegial support and professional development. Moderation will also contribute to improved consistency across teachers.

- Benchmarks: Are teachers’ judgments about learners’ progress and achievement in line with curriculum expectations?

National curricula set out expectations for what learners should know and do at different points in their learning. These may be accompanied by progressions of learning, exemplars and performance indicators. These elaborate on criteria and include learners’ actual performances along with explanations of the features of those performances that contribute to the judgment made about the learning. As nationally developed benchmarks for the curricula, such tools guide teachers’ understandings of expected interpretations of learners’ performances.

Fairness

Fairness is concerned with assessing learners in ways that are appropriate for them, and that recognise the diversity of learners. It ensures that assessment allows all learners to show what they know and can do. It is also important to consider whether some learners may need additional assistance, and what other opportunities learners may benefit from. Fairness is necessary for ethical assessment practice and to give all learners equitable opportunities to succeed in their learning.

Achieving fairer assessment requires flexible conditions and strategies as different learners may have different needs. Flexibility is more acceptable when assessment is used to support individuals’ learning but less acceptable when making decisions about awarding qualifications. Assessment fairness is complex and cannot be ensured through one set of practices. Fairer assessments can be achieved using different conditions and strategies depending on the purpose of the assessment and the learners assessed, including:

- Opportunities to learn: Do all learners have the same opportunity to show what they know and can do?

All learners should have similar and appropriate opportunities to learn. This may relate to what learners experience in their ECE or school settings, and to other social and educational factors that enable learning, including the availability and quality of resources (teachers, learning materials, technology, and so on) and learners’ ability to use them.

- A constructive environment: Do school students feel comfortable when they are assessed?

School students need to see that assessment is worthwhile, or at least necessary, and be respectfully encouraged to participate in assessment in order to demonstrate what they know and can do. This requires high levels of trust and respect between teachers and students, and among peers. Students need to feel safe about demonstrating their learning in an assessment and know their learning will be supported accordingly.

In ECE, children need to experience learning opportunities that allow them to freely explore and show their learning. To enable this, teachers should aim to minimise any factors that might inhibit children from fully showing their learning. This is often achieved through the use of photographs, videos and artifacts of children ‘in action’, and documented later.

- Teacher reflection: Do teachers avoid bias and recognise diversity?

Assessment may be influenced by several factors of which teachers need to be mindful. These include teachers’ assumptions and beliefs that may lead to bias, their openness to the knowledge and learning of diverse learners, and their commitment to fairness. Other factors include thoughtful planning, administration, and interpretation.

- Transparency: Do school students clearly understand what the teacher requires in an assessment?

Are the instructions clear? Are the assessment criteria explicit, clear and shared with students? Transparency makes assessment fairer by reducing irrelevant factors (although this is less relevant for children in ECE).

- Opportunities to demonstrate learning: Do learners have multiple, varied, equitable, and meaningful opportunities to demonstrate their learning?

Multiple opportunities allow teachers to gather sufficient information to make fairer decisions; varied opportunities enable different types of learners to succeed; equitable opportunities, using appropriate accommodations, allow learners to demonstrate what they know and can do; and meaningful opportunities are engaging and challenging without being superficial and impossible.

The relationships between validity, reliability and fairness

Validity, reliability and fairness are interconnected in important ways. Validity is considered to be the most important quality of sound educational assessment and making valid interpretations of learning needs reliable assessment information. But reliable assessment on its own does not necessarily mean that it is assessing what you intend to assess (i.e., it is valid). Reliability then is a necessary but not sufficient condition for validity. Achieving fairness in assessment may impact on both reliability and validity. Thus, optimal assessments balance validity, reliability and fairness to best suit the purposes of the assessment.

References

Darr, C. (2005). A hitchhiker’s guide to validity, Set, 2, pp. 55-56.

Darr, C. (2005). A hitchhiker’s guide to reliability, Set, 3, pp. 59-60.

Tierney, R. D. (2016). Fairness in educational assessment. In M. A. Peters (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory. Singapore: Springer Science+Business Media. DOI 10.1007/978-981-287-532-7_400-1

By Alison Gilmore