Much has been written about the general purposes and principles of assessment to make ‘valued learning visible’ in early childhood education settings, but when it comes to specifically painting a picture of children’s communication competencies, where do we start? Assessing communicative interactions in early childhood settings is critical to supporting children’s learning and development because it allows us both to understand how and why children interact with others and to evaluate the impact of teacher interactions and the environment surrounding those interactions.

Communication is complex, being comprised of many distinct and yet interconnected aspects including social interaction, language comprehension, expressive language and speech. Given the centrality of language to children’s learning and the many areas to consider, it might feel challenging for busy early childhood teachers to think about where to start in documenting children’s communication profiles. Informal assessment is one way for adults to gauge a child’s strengths and weaknesses through the documentation of observations in everyday, play-based contexts. This guide offers a starting point for teachers to informally assess children’s communication skills in early childhood settings by considering two key aspects of communication and suggesting some ways to record initial observations.

Two key aspects of communication: how and why children communicate

Children communicate for a range of different purposes using a variety of modes or forms. From birth, babies give us signals to tell us what they want or need (such as crying if they are hungry), and these signs of communication change and become more elaborate over time as a child learns how to interact socially with others. Thinking about why and how children communicate in their natural, everyday interactions can be a useful starting point for assessing their potential strengths, competencies and challengesii. Understanding why and how a child communicates can help us to provide opportunities to further extend their interactions and learning in early childhood settings.

Why do children communicate?

In seminal research, Halliday identified that children communicate for specific purposes or ‘functions’ from birthiii. Halliday’s research showed that several functions are evident in the ways that babies communicate from before they can talk, and that these same functions continue in the interactions of older children. Halliday proposed that children communicate with others for a range of reasons, including:

- To request

- To protest

- To comment or draw attention to something/someone

- To interact with others

- To seek information or ask questions

- To respond or give information

- To be imaginative

How do children communicate?

In fulfilling their physical, emotional and social reasons for communicating, children use the multimodal means available to them. These forms of expression depend not only on a child’s age and the language(s) they speak but on what is recognised as being meaningful in social and cultural contexts. This is why, in assessing children’s competencies, it is critical to know about patterns of communication used in family homes and communities in order to gauge expectations both inside and outside the early childhood context.

Children communicate in a variety of embodied, nonverbal and verbal ways that can sometimes be subtle or fleeting. These include:

- Body language

- Facial expression

- Eye and eyebrow ‘talk’

- Gestures or signs such as pointing or waving

- Making symbolic noises such as car or animal sounds that represent something

- Visual or sensory expression (such as drawing, painting, building, dancing)

- Vocalisations such as laughing or random play with making sounds

- Spoken words and sentences

- Narrative or stories

It is important to note here that the way a child communicates using a range of signals not only reflects their expressive abilities but can also indicate a child’s comprehension of a situation or conversation. This is another reason why a child’s communication needs to be viewed in context, and in relation to the actions of his or her communicative partners. In carefully observing a child’s embodied and verbal signals in response to others, we can gauge how those responses match up with the questions, comments or actions presented to them. Viewing the child in the context of his or her social interactions, rather than just looking at their strengths or weaknesses in isolation, recognises the holistic, reciprocal nature of communication.

To fully understand the impact of how and why a child communicates, it is also important to think about how effectively they engage socially with others – for example, do they initiate contact, or tend to wait until others approach them? How consistently do they respond to comments, requests or questions? Do they take turns with their peers in small group interactions and how much support is required? Does the child show any signs of confusion, frustration or withdrawal if they cannot understand or make themselves understood? Children initiate, respond and maintain their social interactions with others in a range of different ways, and often without using verbal talk. In this sense, how and why children communicate can be observed in the behaviours they use across different activities and social or cultural settings. We could even go so far to say that all behaviour is communication in one form or another.

Documenting children’s communication competencies: recording your observations

There are many ways to record how and why children communicate as they interact with others, either individually or in groups in early childhood settings. Using multiple methods of documentation will help you to build up a holistic picture of patterns over time. These methods might include:

- Handwritten notes while observing children in their everyday activities. Always record the date, time and a few points about the context (such as the location, people involved, the topic of conversation or activity). Post-it notes can be useful to quickly record specific observations ‘on the fly’, and then added to children’s profiles later

- Taking a language sample by writing down any actions, words or phrases used by the child – this doesn’t need to be long, as even just recording what you hear or see for 1-2 minutes can be very powerful if you do this at regular points in time

- Photos, video clips and audio recordings, which can be useful to capture moments of time to discuss with parents/whānau as an essential part of the assessment process

- Documenting information from parents or family members around communication at home – for example, what language/s or dialects are spoken and by whom? What are the key gestures/words/phrases used by the child at home? Are there any concerns around how the child communicates, such as hearing? What are the important social or cultural forms of communication experienced by the child such as songs or waiata, traditional stories, and so on?

- Keeping notes of what the child tells you about the ways they enjoy expressing themselves, or anything they find difficult

- Taking copies of children’s drawing, art or other forms of sensory expression, and recording what the child tells you about it

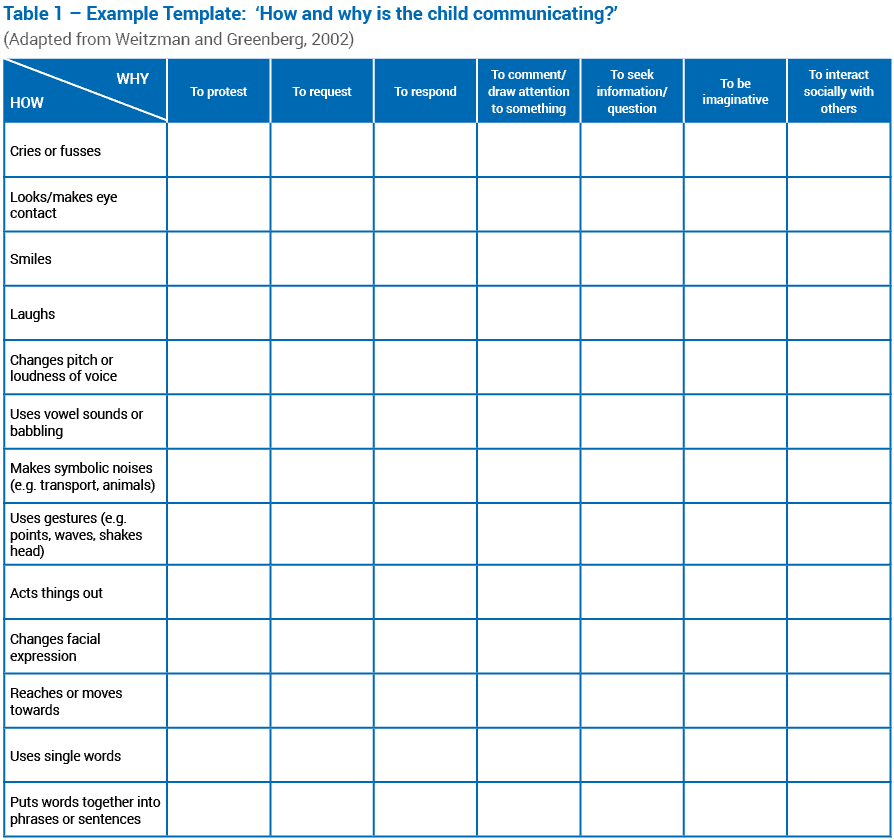

Collating the information gathered from various sources and transferring it into a communication assessment profile is a powerful way to discover how and why a child is communicating, while also documenting subtle changes in progress over time. Transferring your observations into a communication template is one way to keep everything in one place, and also allows you to see if there are any patterns emerging. An example is shown in Table 1. This template can (and should) be adapted and personalised by early childhood settings to reflect their own communication learning priorities

Drawing up a communication profile like this can be a useful tool to show evidence of how and why children are communicating with others now as well as patterns that emerge over time. Use your observational data to record ‘how’ and ‘why’ the child communicates, highlighting points of intersection where ‘how’ and ‘why’ meet (for example, the child requested a turn with the digger (why) by pointing to it (how); the child protested when another child took the cracker off their plate (why) by crying and using a single word ‘no!’ (how). Don’t forget to also keep a note of the context and record the date of your observation. You could use different coloured highlighting tools (online) or pens to show where the ‘how/why’ points intersect. In this way, it is possible to visually show and track a child’s strengths, while also noticing areas that you might not yet have observed. Over time, you will start to see patterns around a child’s strengths as well as areas where they might need further teacher support or strategies if they are struggling to communicate their needs, wants and emotions.

Making sense of your observations

The following questions will help you to make sense of your observations around how and why a child is communicating:

- Are there any clear patterns in how and why the child communicates, such as with certain people, places, things?

- What are the child’s strengths in communicating? For example, do they use gesture and noises more than words? Do they initiate more than they respond?

- What things have we not yet observed in the early childhood setting? (for example, perhaps the child is not using words or sentences in any language yet. This may not necessarily indicate a problem, but could reflect the child’s development, or different languages and styles of interaction in the home and early childhood settings).

- How do observations in the early childhood centre match what the parents or whānau report at home?

- Have the family noticed anything in particular about the child’s hearing, listening, understanding or how they communicate and express themselves with others?

- Over time, has the child’s communication changed and if so, how?

- How do the child’s patterns of communication align with early childhood centre learning outcomes and priorities?

- Does the child show any significant and ongoing signs of frustration, withdrawal or difficulty in engaging with others?

- In what areas of communication does the child need some help?

- What teaching strategies could be used to support the child’s communication (such as giving them extra time to respond, using gestures alongside words, and repeating instructions)?

- Based on our observations of this child so far, what areas of communication will we look out for next, and what teaching supports or strategies could we try, either with individuals or groups of children?

How to identify if further support is needed

Informal assessment of how and why children communicate is a good starting point for providing teachers with valuable evidence for planning and supporting children’s communication skills and progress over time. Much More than Wordsiv is a useful resource that can be used alongside teacher observations for assessing and supporting children’s communication in early childhood settings. In some cases, your informal assessment may reveal an ongoing area of concern in the way a child communicates with others, even after trying various environmental scaffolds and teaching strategies to support the child. If you require further help and advice around assessing or supporting a child’s communication skills and development, you may want to consider a referral to a speech-language therapist. Information about how to locate and access speech-language therapy services in education, health and private practice can be found on the New Zealand Speech-Language Therapists Association (NZSTA) website.

References and recommended reading

Halliday, M. A. K. (1978). Language as social semiotic: The social interpretation of language and meaning. Baltimore: University Park Press.

McLachlan, C. (2018). Te Whāriki revisited: How approaches to assessment can make valued learning visible. He Kupu, 5(3), 45-56.

Ministry of Education. (n.d.). Much more than words. Retrieved from https://seonline.tki.org.nz/Educator-tools/Much-More-than-Words

Ministry of Education. (2017). Te Whāriki: He whāriki mātauranga mō ngā mokopuna o Aotearoa. Early childhood curriculum. Wellington, New Zealand

Weitzman, E., & Greenberg, J. (2002). Learning language and loving it: A guide to promoting children’s social, language and literacy development in early childhood settings (2nd ed.). Toronto: Hanen Centre.

Endnotes

1 Te Whāriki, 2017, p. 63.

2 Weitzman & Greenberg, 2002.

3 Halliday, 1978.

4 Ministry of Education, n.d.

By Amanda White