Retrieval practice is a strategy used for rehearsing already learned information by trying to retrieve it from memory. It is based on what is known as the ‘testing effect’, which found that future long-term memory performance is enhanced when content is practised by testing. While tests are often negatively associated with assessment and performance measurement, in retrieval practice tests are used as a tool for learning and practice rather than as a means to formally assess progress.

The evidence that it works

Retrieval practice tops a list of the most effective evidence-based learning strategies[i] and it has been shown to be effective for students of all ages and subjects. Retrieval practice is often compared to strategies like re-reading or re-studying. Re-reading is a very common method of studying used students, and it is often recommended by teachers as well. Re-reading the book or the notes seems perfectly reasonable, as it involves re-exposing ourselves to previously learned material in order to secure it in our minds. Indeed, we can actually feel the benefit as we are practising this method of rehearsal. However, this method has been found to be ineffective. More accurately, re-reading may be effective in the very short term (defined loosely between minutes and a few days), but is almost entirely ineffective for longer-term recall. The major difference between re-reading and retrieval practice is that, when you re-read, the information is presented to the learner in its entirety from an external source, while with retrieval the learners search for the information in their own minds, following just a cue.

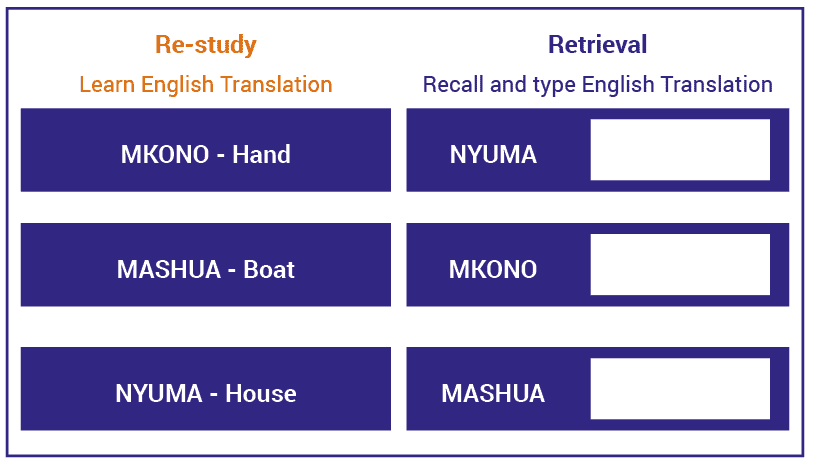

An influential study[ii] clearly demonstrates this point: Karpicke and Roediger had college students learn 40 words in Swahili and their translation to English. The experiment included study phases in which each word appeared next to its translation on a computer screen, and retrieval phases in which the Swahili words appeared and participants were requested to type the English translation if they could recall it. These phases repeated alternately four times each, and all the participants were tested on their memory one week later. The goal of the study was to find out which of the phases, re-study or retrieval, contributed more to long-term performance. To test that, they changed the number of words in each phase for different groups: one group faced twice as many retrieval repetitions than re-study repetitions, and another group experienced it the other way around.

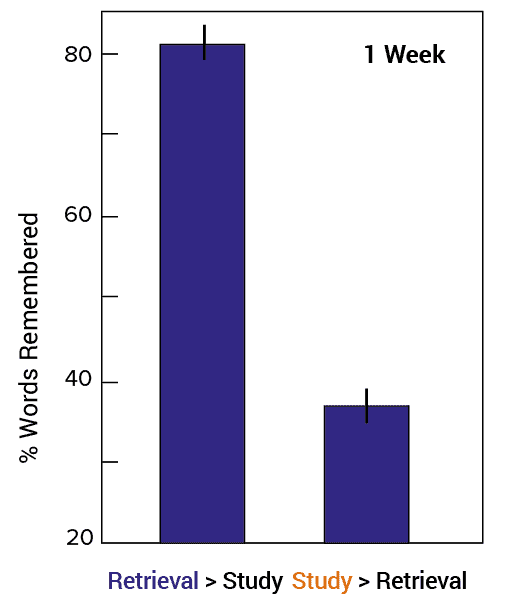

Here is their memory performance after one week: the group that had two-thirds of their study trials in the form of test averaged 8o% of the words, while the group that had two-thirds of their study trials in the form of re-study averaged 36% of the words. Additional experimental groups showed that extra study repetitions did not improve the final recall performance, and were therefore a waste of learning time. This study showed that retrieval or testing is a very effective learning strategy. Many other studies demonstrate the benefits of retrieval practice with more complex stimuli, such as passages of text, different types of materials and within educational settings.

Why does retrieval work?

When we re-study by reviewing or reading over course material or notes, we focus on the information and practically ignore the pathway leading to it in our long-term memory. By contrast, when we try to retrieve memories, we focus on reconstructing the pathway to the stored information and we go over the sequence of neural activities that is required in order to bring a piece of information to mind. When we use retrieval practice, we rehearse the entire pathway, not just the end goal. Much like navigation, knowing the way is as important as knowing the destination.

Retrieval practice is obviously a more effortful task, but the effort is the reason it works. Most students appreciate the importance of practice in acquiring mastery, and, because reviewing the learned information is straightforward and easy, it is often the intuitive choice. But if the end goal is to be able to retrieve the information and use it whenever required, it becomes clear that we need to rehearse just that: retrieving information and using it. Retrieval practice is more challenging than re-studying, but it is the more effective way to practise

How to make retrieval effective

One of the most important considerations in using retrieval practice isto make retrieval effortful. Our mind should work hard, reconstructing partially deconstructed pathways. If retrieval is too easy, it means that nothing was reconstructed and nothing was added. In addition, retrieval is not effortful when it is a concept that we have already mastered, or when it is too soon after the last learning or practice session. The straightforward way to make retrieval practice effective is to space the study repetitions over time.

Another crucial element of retrieval practice is the provision of feedback, as receiving feedback after the retrieval attempt improves learning. Effective feedback should always do two things: it should correct misconceptions and misunderstanding, and reinforce correct responses. It is also important to provide the right level of support. Retrieval practice has been shown to work even with young children, but it may require more structure and support. Students of different ages and those who are at different stages of learning (novices or advanced) in a particular subject or learning area benefit from different types of retrieval activity, such as fill in the blank exercises, multiple choice questions or open questions. One thing to keep in mind is that retrieval practice as a form of practice should come after learning rather than at the time of learning.

How to make it work in the classroom

It is useful to frame retrieval practice as a learning activity, and it can be useful to explicitly explain why retrieval practice is effective. The successful application of retrieval practice relies on:

- the type of activity (for example, a low-stakes quiz)

- how it is framed (for example, is it a surprise quiz or regular morning review routine?)

- how much room we leave for making mistakes and correcting them or providing feedback

It is highly recommended that retrieval practice activities are built into the learning routine in the classroom rather than students using it at home by themselves, as most students will tend to revert to easier strategies such as re-reading. While it may be challenging to make time for a questionnaire or review during the lessons, it is highly likely to be worthwhile. Another reason to use retrieval practice as opposed to an approach like cold-calling or whole-class questioning in the classroom is that it makes the benefits available to all learners. For example, when a teacher asks the whole class a question, generally only a few students volunteer to answer, and it is only the student who actually answers that receives the benefits of retrieval practice. However, when retrieval practice is used during class time as a learning activity in which all students participate individually, it promotes the learning of all students and their ability to learn effectively in the future.

There are a number of technological solutions that can be used for retrieval practice and have the added value of storing the information for formative purposes, such as kahoot!, socrative and plickers.

Recommended further reading

Agarwal, P.K., Roediger, H. L., McDaniel, M. A., & McDermott, K.B. (2020). How to use retrieval practice to improve learning. http://pdf.retrievalpractice.org/RetrievalPracticeGuide.pdf

Brown, P. C., Roediger, H. L., & McDaniel, M. A. (2014). Make it stick. Harvard University Press.

Harvard, B. (2017, September). Color coding recall attempts to assess learning. The Effortful Educator. https://theeffortfuleducator.com/2017/09/14/color-coding-recall-attempts-to-assess-learning/

Newmark. B. (2017, November). Nothing new, it’s a review – on why I killed my starters. https://bennewmark.wordpress.com/2017/11/13/nothing-new-its-a-review-on-why-i-killed-my-starters/

Sumeracki, M. (nd). How to create retrieval practice activities for elementary students. The Learning Scientists. http://www.learningscientists.org/blog/2017/4/6-1

Endnotes

[i] Dunlosky, J. (2013). Strengthening the student toolbox: Study strategies to boost learning. American Educator, 37(3), 12-21. https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/periodicals/dunlosky.pdf

[ii] Karpicke, J. D., & Roediger, H. L. (2008). The critical importance of retrieval for learning. science, 319(5865), 966-968.

http://learninglab.psych.purdue.edu/downloads/2008_Karpicke_Roediger_Science.pdf

By Dr. Efrat Furst