Most people agree that to master a skill we need to practise. However, there are many ways to practise, some of which are more effective than others.

Spaced practice or distributed practice is the idea that practising a particular skill or retrieving particular information is more effective when spread over time, rather than repeated sequentially over a short time period.

Origins of spaced practice

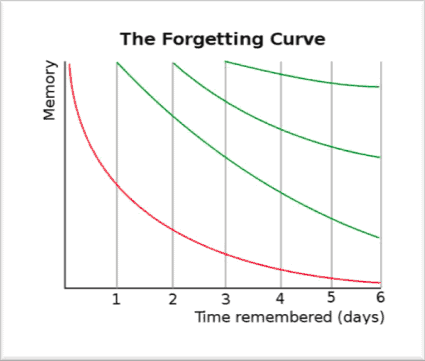

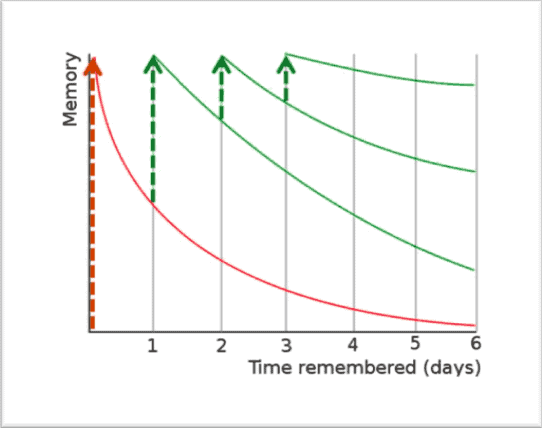

In the late 1890s, the German experimental psychologist, Herman Ebbinghaus, reported the “spacing effect”. He was the first person to describe the forgetting curve, which shows how quickly memories fade after learning. Note the red graph: about 50% is lost after one day.

Practising or rehearsing slows down the forgetting process, with spaced practice much more effective than massed practice (without spaces). Each green line on the graph is a rehearsal, where the memory goes back to 100% and then decays again, but in a more gradual manner.

Why does spacing work?

When memory is encoded and stored in the brain, connections between neurons are formed. Memories are represented by networks of interconnected neurons and when we learn something new, a new network is formed. This process of biological consolidation of memories requires resources and time. Research shows that resting (and, better yet, sleeping) after learning enhances our ability to remember the information. Spacing out the repetitions may allow the brain machinery to work without interference between the two events.

Another reason why spacing is effective is that, over time, memories decay and becomes less and less accessible. By attempting to relearn something after a period of time we are actually reconstructing the information itself, and even more importantly, we are reconstructing the pathways that lead to it, so that it will be more accessible next time. We can think of the initial learning in terms of building a house. Then, every time we want to get to the house we have to reconstruct the route leading to it, and sometimes find a new route. With time, we mostly forget the routes, and must reconstruct them to reach the house. So the reason spacing is effective, according to this explanation, is that it triggers active effortful reconstruction of the retrieval pathways, in other words spacing induces more effective retrieval practice.

Another advantage for spaced learning is that the passage of time also changes the context of learning. If time has passed since our last practice, we will most likely approach the information in a different way, and use different cues or triggers. Using the house analogy, it is like learning several different routes to the house from different initial locations, which ultimately will allow us to get there easily, no matter where we are. By practising in varied contexts, we are making sure the information will be much more accessible, in different situations and with different cues.

The bottom line is that practice should be effortful to be effective. We should concentrate on reconstructing pathways, not just revisiting the information. By spacing the repetitions we are making it harder on ourselves, but the effortful reconstruction process is what makes practice beneficial since we are building stronger pathways to the memory. Rest is also crucial to memory. Following the effort of reconstruction it is better to rest in order to allow the pathways to consolidate. A second immediate repetition is not challenging enough and consequently not so effective. In addition, it may interfere with the consolidation processes of the previous attempt. To apply effective spaced practice we should work hard and then have a good rest.

What are the recommended schedules?

The answer to this question depends on several factors, including the level of difficulty of the material, how familiar it is for the learner, and how much it already has been practised. Using the routes analogy, it depends on how complicated the route is, whether it goes through locations that we already know, and how many times we have taken it before.

It is most advantageous to rehearse when it has decayed significantly but not completely. We want reconstruction to be effortful but also effective. Take a look at the forgetting curve again below, the first rehearsal after one day should reconstruct about 50% of the learned information. After a few repetitions, the decay is slower, and hence larger spaces can be used.

Another question that should guide our thinking about the spacing schedule is when is the information expected to be used again? This question is highly relevant to educational settings: do we teach for the test, or do we teach for life?

Researchers have found a clear relationship between the spaces between studies and time to optimal performance.2 Short spacing times (seconds and minutes) produce short-term optimal performance, while longer spaces produce long-term optimal performance. Researchers have concluded that at least one day is required between repetitions to maximise long term retention (weeks and months), and that longer spaces (e.g. 1 month) can produce even longer-term effects.

Putting this information together, the conclusions are:

- Repeatedly rehearsing the material in the same study session will not have long-term effects and may even impair learning. In other words, cramming is not effective for the long term.

- It is recommended to repeat the same material on different days in order to produce long-term results.

- As we practise more, the information becomes more stable and more accessible. It means that:

- It will ‘survive’ longer gaps.

- Subsequent repetitions will take much less effort.

How does it work in the classroom?

Everything that we learn should be practised effectively, or it becomes inaccessible. Practice is obviously an important part of the teaching process, and to maximise its effect we should seriously consider the schedule of revisions. Once the information is acquired it should be revisited in increasing spaces, starting with days and weeks, and then spreading out to months and years.

One barrier for learners is that frequent repetitions are easy to do, while repeating older material is much harder, and may feel extremely vague and even impossible to reconstruct. Understanding the benefits of spaced learning as teachers, we need to take these challenges into consideration when planning our teaching routines.

It is illuminating to compare spaced practice in the classroom to practice routines that are common in other fields. For example, when we practise music or sports, we often repeat older exercises and more basic ones on a routine basis. We go back to older musical pieces, or older exercises. Even at the highest levels, musicians and athletes still practise basic skills. We should adopt the same thinking in regard to English, maths, history and any other fields of study.

What does it require?

- Planning ahead To systematically introduce reviews of previously learned information be specific about content and schedule some form of review in each lesson. Here is an example for a daily plan by maths teacher Anna Vance.

- Building a routine Developing a positive attitude towards spaced practice requires practice in order to realise that what seems impossible at first is doable, and that it becomes considerably quicker and easier in subsequent attempts. It may be worth explicitly explaining to learners why they are undertaking a particular activity. In this blog post Blake Harvard, a secondary school psychology teacher, shows how he uses spacing in the classroom with very simple reviews, and the simple method he devised to prove to his students that the method is working.

- Supporting the effort There are simple ways teachers can support the review process by adjusting it to the students’ level. One practical example is to use the Leitner system for effective use of flash cards explained by Thomas Frank in this 8-minute video about spaced practice. This method allows every student to focus each day on the cards that need the most attention. The method by Blake Harvard in the previous example also allows every student to practise to their best ability each time, correct themselves and improve in the next round.

- Differentiating learning and practice The practice phase that should be distinguished from the initial learning process:

- Learning is when a concept is presented, defined, explained and demonstrated. It is the building phase and it requires working memory resources to build the new information on the basis of prior knowledge. At this stage, to reduce cognitive load it is helpful to repeat the same points several times in the same lesson.

- In a later practice phase the new concept (or skill) is established, and it is now time to maintain what was built, as well as creating and maintaining access pathways to it. This is when more challenging and effortful practice methods are appropriate.

The importance of interleaved practice

Interleaving suggests mixing up the order of tasks, instead of repeating the same task over and over again.

The benefits of interleaving are related to the contribution of both spaced and retrieval practice: when we mix up the order of learning, we create spaces and distractions between two repetitions of the same material, which force the learners to re-engage in the material and to invest effort in reconstructing the information. There are findings that support the benefits of interleaving, and the best examples are from maths practice: for example, instead of practising dozens of addition problems and then dozens of subtraction problems, addition and subtraction problems should be interleaved for more effective practice. You can read more about this in this short review with examples. Interleaving is another way to make the practice distributed, effortful and varied.

Additional reading

More about spacing, interleaving (and retrieval practice) in the book “Make it Stick: The Science of Successful Learning” by Brown, Roediger and McDaniel.

Brown, P. C., Roediger, H. L., & McDaniel, M. A. (2014). Make it stick. Harvard University Press.

The website by “The Learning Scientists” Dr. Yana Weinstein and Dr. Megan Sumeracki, is a very good sources for evidence based information about these learning strategies. Specifically this is a collection of teachers’ blogs about practicing spacing effect in the classroom, and the downloadable designed posters on Spaced Practice and Interleaving.

References:

1 Dunlosky, J. (2013). Strengthening the student toolbox: Study strategies to boost learning. American Educator, 37(3), 12-21. https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/periodicals/dunlosky.pdf

2 Cepeda, N. J., Pashler, H., Vul, E., Wixted, J. T., & Rohrer, D. (2006). Distributed practice in verbal recall tasks: A review and quantitative synthesis. Psychological bulletin, 132(3), 354.

Rohrer, D., Dedrick, R. F., Agarwal, P. K. (2017) Interleaved Mathematics Practice Giving Students a Chance to Learn What They Need to Know. http://pdf.retrievalpractice.org/InterleavingGuide.pdf

Referenced Blogs:

Daily Structure by Anna Vance via Math-A Mathland http://typeamathland.blogspot.co.uk/2017/07/daily-structure.html

Easy Application of Spaced Practice in the Classroom by Blake Harvard via The Effortful Educator https://theeffortfuleducator.com/2017/10/22/easy-application-of-spaced-practice-in-the-classroom/