The environment has long been referred to as the ‘third teacher’ but what does this mean for the provision of inclusive, play-based outdoor learning experiences that promote exploration and support children’s competence?

The importance of outdoor play

The unique characteristics and stimuli of the outdoor environment provide different play opportunities that cannot be replicated indoors. Being outdoors, especially in natural outdoor learning environments, provides the opportunity for open-ended interactions, spontaneity, exploration, discovery, risk-taking, and connection with nature. In outdoor settings, children generally move more, sit less and engage in play for more sustained periods. Depending on the location and design of the outdoor environment, they potentially have more space and freedom for large and loud movement play. They engage in more moderate to vigorous physical activity, have greater opportunities to gain mastery over a wide range of gross and fine motor skills, and develop better motor co-ordination.

Being outdoors provides the freedom to explore and manipulate the environment though rich, multisensory experiences in the natural environment. Children experience independence and agency as they utilise nature’s loose parts to engage in imaginative, co-operative and creative social play1. There is also well-documented evidence that green spaces have positive effects on the physical and mental health of children and adults alike. Contact with nature is associated with self-regulation, and physical activity in natural settings greatly improves positive emotions, self-esteem and behaviours. Other physical and mental health benefits include vitamin D production from sunlight, better concentration, less impulsivity, less stress, and a reduction in anxiety and depressive symptoms1.

Importantly, outdoor environments provide an authentic context for children to learn about the world and their place within it. Environments that include natural elements, in particular, provide endless opportunities to learn about the world in a meaningful way as the outdoor environment is constantly changing in response to the weather, seasons, time of day and the interaction between humans and the environment. Through these experiences, children develop environmental awareness and a sense of connection to nature.

Thinking about outdoor play environment provision

Engaging outdoor learning spaces offer stimulating resources and rich play-based learning opportunities that are relevant to all children’s interests, capabilities, cultures and communities, and support children to explore and take risks. The physical features and characteristics of the outdoor environment —such as space, playground design, access to natural environments and availability of quality equipment and resources—influence children’s engagement in sustained, meaningful outdoor play experiences. One way of thinking about the physical features and characteristics of the outdoor environment is by considering the affordances it offers—in other words, the properties of the physical environment that invite us to do something or to undertake a particular action2. Affordances within the environment are dynamic and unique to each person, and vary in response to the individual’s changing size, strength, capabilities and motivation. Children will perceive what they can do in the environment in relation to their individual characteristics. Hence, the same feature of the environment will afford different behaviours for different individuals or in different contexts3. For example, a small tree might afford climbing for a young child but not for a large adult. Likewise, a tree may afford shelter in summer but not in winter when its branches are bare or allow children to collect the fallen leaves in autumn.

In thinking about affordances that support play-based learning in the outdoor environment, various factors may influence the design of the environment depending on whether it has been intentionally designed from the outset as a space for children’s play and learning or has been adapted (and potentially constrained) to fit within an environment not originally intended for children4. Research by Susan Herrington and Chandra Lesmeister4 identified seven characteristics of outdoor environments that exemplify environments that best support children’s exploration, play and learning in early childhood education settings. These include:

- Character: the overall feel and design intent of the outdoor play space

- Context: the small world of the play space itself, the larger landscape that surrounds the centre, and how they interact with each other, including the overall space as well as micro-climatic conditions, ecology and indigenous plantings

- Connectivity: the physical, visual, and cognitive connectivity of the playspace itself, including visual and physical connectivity between the indoors and outdoors, between areas within the outdoor environment, and between the centre and surrounding neighbourhood

- Change: in relation to how the whole play space changes over time in response to changing weather and seasons and to children’s changing interests and needs, providing different sized spaces for different kinds of play and experiences as well as access to materials and resources

- Chance: opportunities for the child to create, manipulate and leave an impression on the playspace through open-endedness, flexibility, spontaneous exploration and discovery

- Clarity: in terms of the physical layout and navigation within the environment, such as clear entries and exits to different zones/play spaces, ease of setting up and packing away, adequate storage, and awareness of the soundscape

- Challenge: the physical and cognitive possibilities for children to test their limits and expand their capabilities, including graduated challenges with several levels of difficulty

Considerations for the design of outdoor spaces

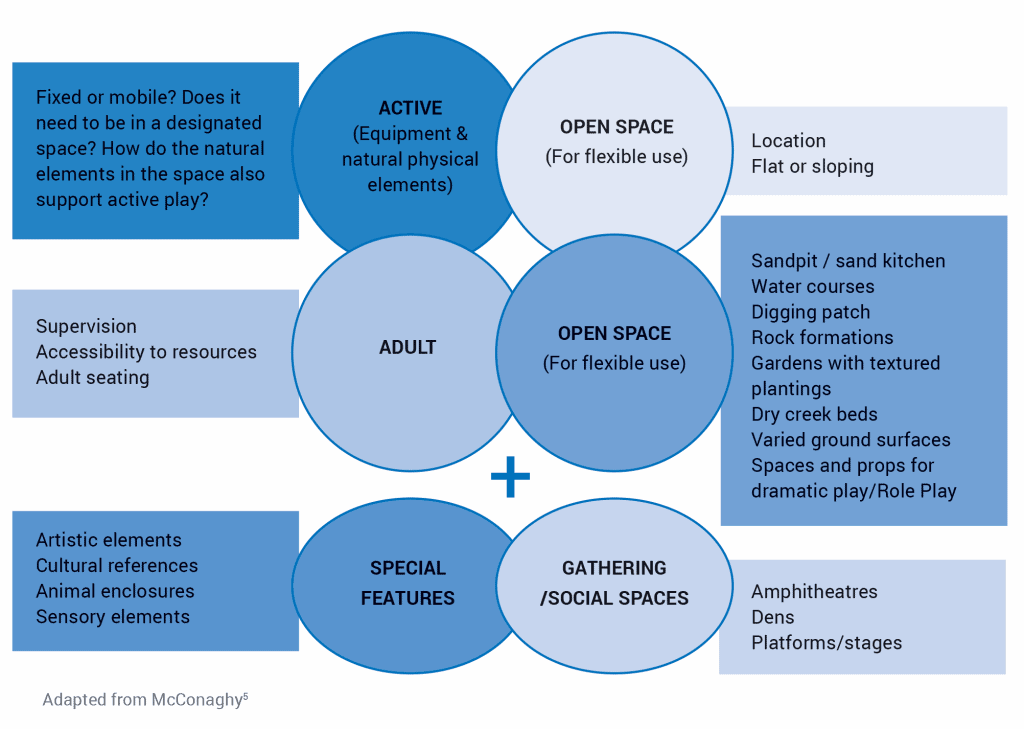

The seven characteristics listed above contribute to the provision of rich outdoor learning spaces. When thinking about the design of outdoor spaces, it is useful to consider these characteristics in relation to the variables summarised in the diagram below:

Although outdoor spaces potentially provide the opportunity for children to engage in active play, there is a growing body of research evidence6 that children in early childhood settings do not meet the daily recommend levels of physical activity, so the first two design elements in the diagram, active areas and open spaces, are very important7. Moveable equipment is a common feature of the outdoor environment and is preferable to fixed equipment, which generally provides less flexibility and cannot be adapted to respond to children’s changing capabilities and interests, thus limiting the possibilities for challenging physical play8. It is also useful to consider how the natural characteristics or elements within the physical environment support active play – are there rocks to scramble over, trees to climb, logs to balance on, and varied ground surfaces and levels to negotiate? Is the space flat or are there areas where the ground is sloping to allow children to experience the differences, which influences their balance and movement patterns? Open space provides the room for more active games and flexible use of the space, whether for running or ball games, rough and tumble play, dramatic play or block building.

Creative and explorative elements such as sandpits, watercourses, rock formations, textured planting and varied ground surfaces like grass, pebbles and bark, are also important. These items invite exploration and creativity and provide a supply of natural loose parts for children to use in their play, encouraging imagination and symbolic play. Social spaces such as dens/cubbies, platforms and amphitheatres provide spaces for children and adults to gather as well as spaces for dramatic play.

The inclusion of special features can provide further opportunities for play-based learning. These might include cultural references that reflect the diversity of the children and community, aesthetic and artistic elements such as mosaic designs created with pebbles or tiles in pathways, or decorative water containers such as bird baths to attract animal life as well as animal enclosures to enable children to learn to care for animals such as rabbits or chickens. Finally, the space also needs to consider the adults in the environment, not just the children. It needs to be an environment that is comfortable for adults as well as being easy to supervise and set up experiences for children in.

Most importantly, there needs to be access to a range of experiences that provide diversity for the children using the space. Inclusive environments allow flexible use to enable children to adapt it in response to their changing interests and capabilities. Children become more deeply involved when they have something that is new and unusual for them to explore and the dynamic characteristics of natural outdoor environments provide this opportunity. One way of achieving this is through the provision of stimulating resources, such as loose parts (both recycled objects as well as natural materials collected from the environment), which are accessible and open-ended so they can be used, moved and combined in a variety of ways. Importantly, teachers should ensure that children have time and freedom to become deeply involved in activities.

Outdoor spaces and connecting with nature

Outdoor environments provide an authentic context for promoting environmental responsibility in which children (and adults) develop environmental awareness and an appreciation of the natural environment, and engage in ongoing environmental education. Teaching outdoors in a natural environment promotes an appreciation of and lifelong connectedness to the environment. It allows kaiako to recognise the relationship mokopuna have with the environment and support tamariki in fulfilling their responsibilities as kaitiaki of the environment9.

A study by Judith Cheng and Martha Monroe10 measuring children’s enjoyment of nature, empathy for creatures, sense of oneness, and sense of responsibility revealed that children’s connection to nature, previous experiences in nature, perceived family (and/or teacher) values towards nature, and perceived self–efficacy positively influenced their interest in environmentally friendly behaviours. When children are provided with an opportunity to develop a sense of wonder, they can make rapid advancements in developing ecological understanding, especially if nurtured by an attentive adult who notices what arouses children’s curiosity and listens to the child’s questions and observations about the world around them in order to identify learning that is intrinsically motivated. Children need to care enough to create a positive relationship with the earth and others, and they need to build a sense of belonging in the environment for this to occur11. Children’s agency, sense of belonging and eco-literacy are promoted through opportunities to:

- Experience unstructured time outdoors – freedom to autonomously explore the environment, time to ‘be’ and to contemplate, in a natural setting

- Develop a sense of wonder about the natural world through exploration and discovery and observing changes in an environment over time

- Develop scientific processes of investigation and experimentation

- Develop varied learning experiences integrating many knowledge areas such as scientific concepts, numeracy skills, and vocabulary and descriptive language

- Develop collaborative, investigative and critical thinking skills, use tools, and begin to develop practical skills in caring for the environment

Adult roles and relationships

The perception of the adult role in the outdoor environment greatly influences the learning opportunities that children experience. The cultural style of interactions between teachers and children and pedagogical practices are an important part of supporting children’s play, exploration and active learning. Sustained, shared thinking is one key to helping develop children’s thinking and problem-solving skills. Outdoor spaces provide untold opportunities for such thinking, so teachers need to plan environments that allow us to take advantage of these opportunities. In this regard, critical reflection on learning and teaching is crucial. To guide reflection, teachers may ask themselves:

- What might children do in this space?

- What loose materials or resources might be added to the space to enhance and challenge the child’s knowledge and/or skills?

- How can we learn here?

- What might be the adult’s role in this situation?

- How can we continue our learning journey?

Teachers need to find a balance between child-initiated/child-led, child-initiated/adult-guided, adult-initiated/child-led, and adult-initiated/adult-led experiences that are appropriate to the context and learning goals/objectives. Across this continuum of adult roles in children’s play, teachers utilise a range of strategies for supporting children’s play and learning from observing, resourcing, facilitating, scaffolding, co-constructing, sustained shared thinking, and direct instruction.

Expanding outdoor play provision beyond the setting

The location of some settings may mean that they have less capacity to provide rich outdoor learning experiences within the centre itself. For those with limited outdoor space, going on local excursions or participating in and contributing to community events can help children connect with the community and engage with natural environments. In recent years, there has been growing interest in outdoor programs modelled on the outdoor preschools and forest schools from Scandinavia and the UK, providing children with sustained periods in natural settings such as urban bush parks and national parks, rainforests, waterways, beaches and foreshores. These approaches focus on delivering hands-on learning experiences in a local natural setting and are designed to support holistic development and foster resilience, confidence, independence and creativity in learners, both children and adults alike12.

Whilst outdoor preschool programs provide opportunities for children to spend sustained periods in nature, such programs or ready access to natural environments are not always possible. This does not mean that community spaces cannot be used to expand opportunities for learning outdoors. Utilising local community playgrounds and green spaces, no matter how small, may provide opportunities to expand children’s experiences beyond those provided at the centre.

Another way of involving children in the community is through community gardens, which many local councils have set up in public spaces. Engaging in such gardening projects can support children’s holistic development and provide opportunities for being physically active as well as building relationships with the community. Children can also learn new skills, have fun, play and develop self-confidence by tending to plants and growing their own food.

Further reading

Casey, T. (2007). Environments for outdoor play: A practical guide to making space for children. London: Sage.

Little, H., Elliott, S., & Wyver, S. (2017). Outdoor learning environments: Spaces for exploration, discovery and risk-taking in the early year. Melbourne: Taylor & Francis.

Warden, C. (2015). Learning with nature: Embedding outdoor practice. London: Sage.

References

1. Chawla, L. (2015). Benefits of nature contact for children. Journal of Planning Literature, 30(4), 433-452. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412215595441

2. Heft, H. (1988). Affordances of children’s environments: A functional approach to environmental description. Children’s Environments Quarterly, 5(1), 29–37. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41514683

3. Wyver, S., & Little, H. (2018). Early childhood education environments: Affordances for risk-taking and physical activity in play. In H. Brewer & M, Renck Jalongo (Eds), Physical activity and health promotion in the early years. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

4. Herrington, S., & Lesmeister, C. (2006). The design of landscapes at child-care centers: Seven Cs. Landscape Research, 31(1), 63-82. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/01426390500448575

5. McConaghy, R. (2008). Designing natural playspaces: Principles. In S. Elliott (Ed.), The outdoor playspace naturally for children birth to five years. Sydney: Pademelon Press.

6. Reilly, J. (2010). Low levels of objectively measured physical activity in preschoolers in child care. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 42(3), 502-507.

7. Tonge, K., Jones, R., & Okely, A. (2016). Correlates of children’s objectively measured physical activity and sedentary behavior in early childhood education and care services: A systematic review. Faculty of Social Sciences – Papers, 2366. https://ro.uow.edu.au/sspapers/2366

8. Little, H., Wyver, S., & Gibson, F. (2011): The influence of play context and adult attitudes on young children’s physical risk‐taking during outdoor play. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 19(1), 113-131. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2011.548959

9. Ministry of Education (2017). Te Whāriki. He whāriki mātauranga mō ngā mokopuna o Aotearoa: Early childhood curriculum. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

10. Cheng, J., & Monroe, M. (2012). Connection to nature: Children’s affective attitude toward nature. Environment and Behaviour, 44(1), 31-49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916510385082

11. Mackey, G. (2014). Valuing agency in young children. In J. Davis & S. Elliott (Eds), Research in early childhood education for sustainability: International perspectives and provocations. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

12. Elliott, S., & Chancellor, B. (2014). From forest school to bush kinder: An inspirational approach to preschool provision in Australia. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 39(4), 45-53. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/183693911403900407

By Dr Helen Little