Since the second half of the twentieth century, music education in schools has seen a gradual shift away from a musical appreciation approach that was common to throughout most of the twentieth century, towards a more practical approach to teaching, learning, and assessing music. There has been ongoing debate among music educationalists as to whether music education should emphasise listening and theory or playing and performing. However, if one of the objectives of music education is to provide students with both an understanding of and experiences in and with sound so that they can learn to express themselves musically, it stands to reason that students need to engage with both music conceptual knowledge and practice. Therefore, while the turn towards more practice-focused programmes was both welcome and necessary, it is also important to ensure that practice does not supplant theoretical and conceptual knowledge. Ideally, the two types of knowledge complement each other.

As described in Music education in schools, the shift towards music as practice runs the risk of sidelining the ‘knowledge-that’ required for deep learning[1]. For example, if music focuses only on procedural skills without reference to knowledge-that (theoretical knowledge), students may well be short-changed as they do not have access to or at least awareness of the knowledge about how music works. For example, students may be taught a number of songs on the ukulele, which, if done well, is likely to be an engaging and rewarding experience. However, if concepts such as keys, chords, harmony, melody, and so on are not also introduced, learning the ukulele can become context-bound rather than an experience that can open up other forms of experience and learning[2]. This is not to say that music theory and conceptual knowledge should dominate the content and pedagogy of classrooms, but rather that it should be integrated into creative, music-making activities such as composition.

There is considerable research from social realism and cognitive science that suggests the need to recalibrate the balance between ‘knowledge-that’ and ‘know-how-to’ if we want deep learning to occur. Imagine a scenario where a teacher wants to develop students’ listening capabilities to utilise in their music making – in other words, to be able to listen beyond a surface level and, over time, become musical critical thinkers. Students first need to listen to and recall a lot of different types of music. Secondly, they need to develop fluency with a range of music-specific concepts and language that describe musical processes and phenomenon[3]. Thirdly, students need to find out what has been written about the significance of the music in which they are particularly interested within its stylistic field. These three aspects involve using concepts as the conduit of learning. In other words, if a student wants to understand, share their understanding, and argue in favour for a particular piece of music, they need to be able to aurally perceive how the music is constructed and creates its affects, describe these aspects, and then devise an argument in the music’s favour. The student might need to call on concepts such as chordal juxtaposition, regular and irregular phrase lengths, timbral combinations, changes of meter, and so on; to put what they hear into words and to form their argument about why this music is worthy of study.

This type of criticality cannot emerge without a great deal of listening experience (the musical equivalent of learning ‘content’ and ‘facts’ stored in the long-term memory), fluency with the specialised conceptual language of the subject, and putting this growing knowledge to use in performing, composing, arranging, and so on. Cognitive science research indicates that students need to encounter lots of factual content which is ordered and categorised through the main concepts of the subject. If our curriculum is predominantly a practice-based one, focused on the ‘know-how-to’ of performing and composing, it is important also to teach the ‘knowledge-that’ (conceptual knowledge) that can deepen the knowledge of the practice.

Ideally, the two forms of knowledge go hand-in-hand and enhance each other, although there is always more pedagogical challenge with how to approach music theory in ways that do not turn students off its importance. In this regard, it is advisable that music lessons begin with action and sound, and that concepts are brought into learning conversations as they are required. In the popular Musical Futures approach primarily used at intermediate and lower secondary school, students are given a high level of control over content selection, sequence, and pace of learning, with an emphasis on applied knowledge (know-how-to) as they learn to play songs of their own choice in friendship groups. Theoretical knowledge (knowledge-that) only appears when it is needed, if at all. An expert teacher may utilise the Musical Futures approach as a mechanism for motivation and practical engagement in the junior levels of secondary school and then, over time, may gradually reveal the concepts (knowledge-that) embedded in the music and the musicking. Rhythm games, learning popular songs with ukulele or guitar, and composing using sequencing software are all excellent content for the development of musical know-how-to and knowledge-that required for deep learning. Ideally, theory should be embedded in and emerge from practice, so theory’s meaning and use are made clear to students, rather than theory being approached as something that is abstract and acquired from a book.

Lesson exemplar: Introduction to chords on the ukulele

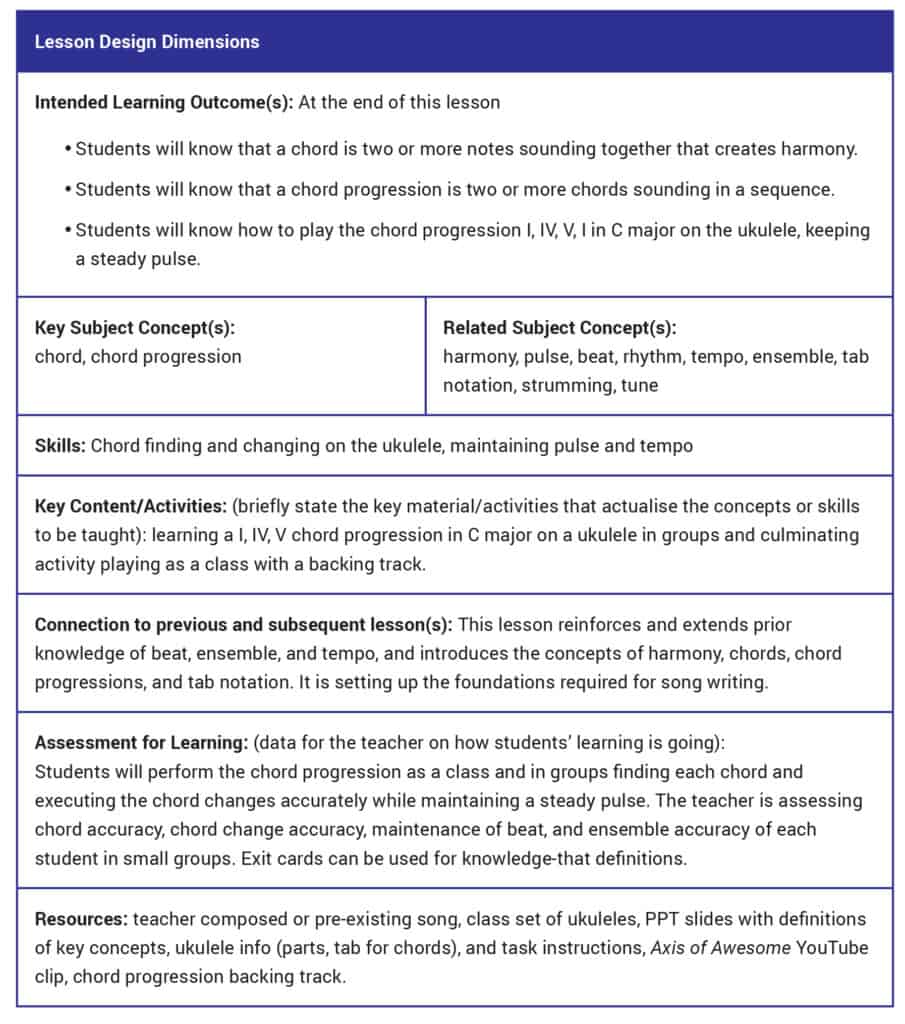

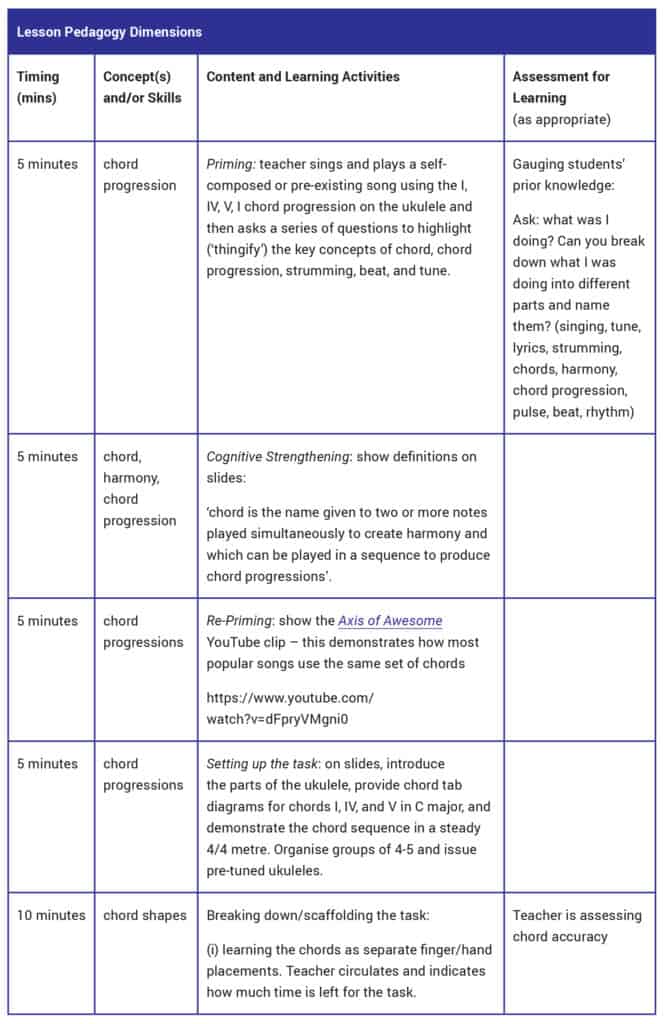

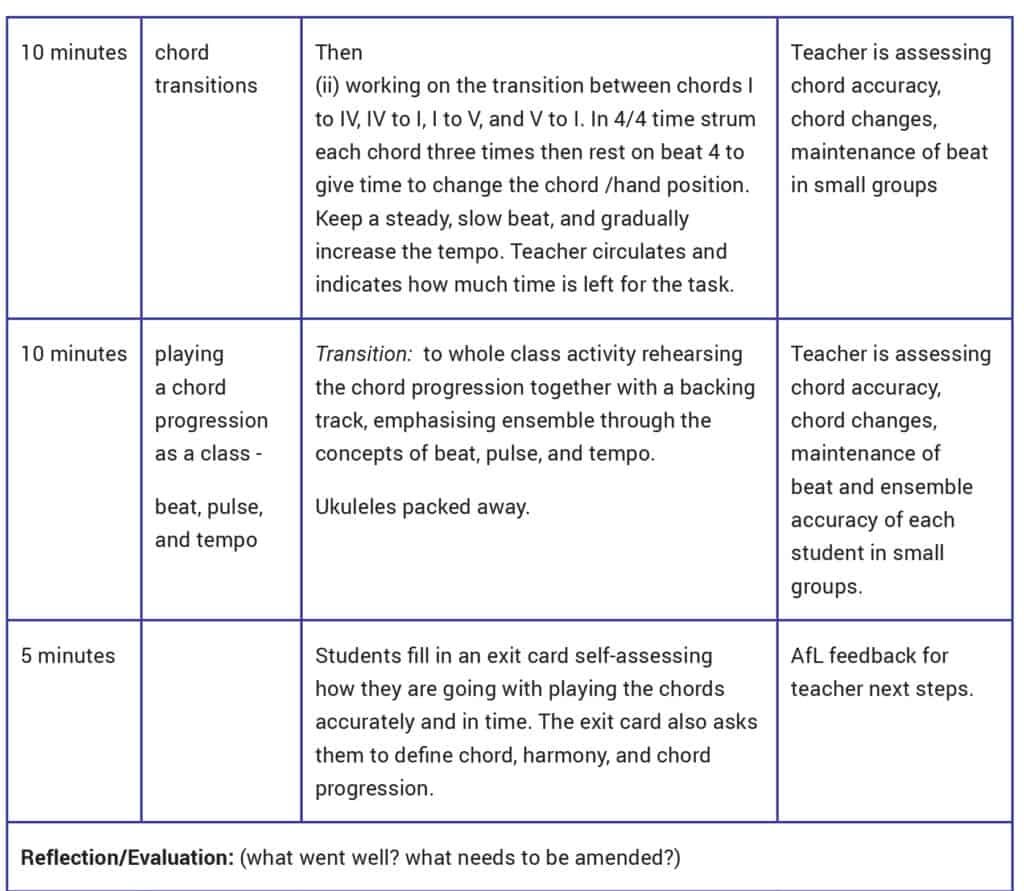

Planning for teaching should start with the key question: ‘what is it I want my students to learn?’ To enable deep learning, lesson design needs to clarify the subject concepts that underpin the chosen topic. For example, in the lesson outlined below for Year 9 or Year 10 music, the goal is to teach the class to play chords on the ukulele. This is fun and interesting in itself, but teachers can also use this activity as a means to increase students’ understanding about chords, chord progressions, and harmony en route to composing their own songs. The deeper level of learning is about the concepts – in this case, chords and chord progressions – which are generalisable subject concepts that can be applied to many different styles of music and many different learning contexts such as composing, performing, and analysing. In this way, the lesson is not only about learning to play chords on the ukulele, but also about other equally important empowering music knowledge such as understanding how harmony, realised as progressions of chords, generates form and structure in music.

In the sample music lesson outlined below, students explore the main concepts of chord and chord progression (both quite dense ‘knowledge-that’ concepts made up of related superordinate and subordinate concepts) and the skill of chord finding and playing a chord progression with a regular pulse on the ukulele – ‘know-how-to’. The key argument in this approach to lesson design is that it is necessary to differentiate between knowledge-that – the concepts and content – and the skills and competencies – know-how-to – in order to make sure that each is well taught and that they are brought together. Teaching only skills limits students’ wider understanding of how music actually works, while teaching only how things work without making music fails to recognise music as an aural and practice-based phenomenon. First and foremost, we must make sounds and make music, and then we can bring conceptual understanding to what we do.

Glossary

Articulation: the way in which a sound is attacked or sounded

Dynamics: how (relatively) loudly or softly music is played

Graphic notation: the representation of sounds and form through graphic means rather than using traditional notes on a staff

Musicianship: musical intelligence, or the ability to engage with and respond to music

Pitch: how (relatively) high or low a note is

Staff: the set of five horizontal lines used in typical Western musical notation

Timbre: the tone colour or quality of a sound

Tab (tablature) notation: a diagrammatic from of notation that indicates where the fingers are placed to generate a chord on a guitar or ukulele.

Useful resources

Ministry of Education. Into Music series: Volume 1 (2001), Volume 2 (2002), and Volume 3 (2003).

Ministry of Education (1992). Music education: Standard two to form two: A handbook for teachers. Wellington: Learning Media.

Regelski, T. (2004). Teaching general music in grades 4-8: A musicianship approach. Oxford University Press.

Endnotes

[1] McPhail, G. (2016). The future just happened: Lessons for 21st-century learning from the secondary school music classroom. Curriculum Matters, 12, 8-28.

[2] Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and Education. New York: Macmillan Company.

[3] I call this ‘thingification’. ‘Thingification’ occurs when we name things, usually as concepts: for example, we might hear certain things happening in a piece of music (such as syncopated rhythms or loud dynamics), but until we have them pointed out and have the teacher introduce the specialised language for that thing, we have not ‘thingified’ it! Having specialised language gives the student power to hear and talk about things.

By Dr Graham McPhail