This resource provides an introduction to evidence-based strategies that can be used for teaching autistic students in primary school settings. The strategies discussed are intended to provide teachers with generalised information. It is important to remember that each autistic student will have their own individual needs, and strategies will need to be tailored to that student on a case by case basis.

What is autism?

Autism is a neurodevelopmental difference that affects a person’s social interaction, behaviour and ways of communicating and interacting. The way that autism is defined and described has changed a great deal since it was first identified in the 1940s[1]. Presently, the correct diagnostic label is Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). However, this label can be perceived as offensive by autistic people and their families, and reinforce the negative stereotype that autism means something is wrong and in need of curing. Autism, Autistic Spectrum Conditions [ASC], or autism spectrum are preferrable terms[2].

Some common characteristics associated with autism include specialised and intense interests, a different style of social engagement, and difficulty adjusting to unexpected change or unfamiliar routines. As there is a spectrum of differences related to autism, the range of characteristics that describe an autistic individual varies widely. Although there are common traits associated with autism, it is important to remember that no two autistic people are the same. For a more detailed overview of autism, see An introduction to autism.

Supporting autistic students in primary school classrooms

Autistic students have brains that are able to make many diffuse neural connections at one time. This unique potential for diverse connections leads autistic individuals to have very busy brains, which may support highly focused and specialised interests, and bring a unique perspective to the class. When autistic students are able to bring their areas of special interest into the classroom, it can be a powerful way to support them to draw and build on their strengths in the school setting. Autistic students often have extensive knowledge about their areas of interest, and are able to focus intently on them for long periods. Autistic students may also experience difficulties with unexpected changes and transitions between activities, as well as cognitive and sensory overload when there is too much going on around them[3].

As autism describes a complex spectrum of differences, there is no single approach to meeting the needs of all autistic students. Teaching strategies need to be adapted based on a student’s individual needs, the resources available (such as teacher aide assistance), and the educational setting. Some of the most effective and research-proven interventions for teaching autistic students are those that are highly structured. Structured teaching approaches cater to individual student needs and address common sources of anxiety by providing predictability and routine[4]. Two key elements of structured teaching approaches are the organisation of the physical environment and the use of visual supports.

The physical environment

Attending to the organisational and sensory aspects of the physical environment is a key part of supporting students to understand and make meaning of school and the classroom environment.

Clear and consistent organisation of classroom spaces. Clear organisation provides the student with information about where specific activities occur in the classroom and what resources may be used in those areas. This can be achieved by arranging the furniture clearly, adding visual labels for each area in the classroom, and organising resources logically to align with the purpose of the designated space, such as placing books in a library corner where group reading may occur. Autistic students often have a strong visual memory, so using visual supports around the classroom allows them to draw on their areas of strength.

The flow of movement within the classroom space is also important. Creating logical visual pathways for transitioning between learning areas and activities within the space is beneficial. Transitions work best when there are fewer physical obstacles. This might involve ensuring that students head in the same direction rather than against one another, that they do not have to travel around furniture or objects, and that the next activity to move to is nearby.

Attending to sensory needs. Autistic students may regulate and process sensory information in different ways, which may involve over-sensitivity or under-sensitivity to sounds, sights, smells, touch, taste, balance and awareness of their bodies. Students with under-sensitivity to sensory information may require extra sensory input. For example, students with an under-sensitivity in balance (vestibular) may benefit from rocking, swinging, bouncing, or similar kinds of vestibular input. Classroom teachers should consider environmental factors that may disturb students with specific sensory needs, such as loud noises, bright lights, crowded spaces, or classrooms that are overly decorated. If possible, additional quiet areas or break out rooms can be utilised when the classroom becomes over-stimulating, triggers the student’s anxiety, or is just too overwhelming for the student.

For teachers in modern or innovative learning environments, it is important to consider how the open layout and flexibility of the physical space may affect student engagement, behaviour, and anxiety. Some autistic students can cope in these types of learning environments, while others may require a designated safe space to give them a sense of predictability and control. For example, a quiet or individual work area may be set up within the space for the student to use when they are overwhelmed. Alternatively, this area could be used as a focused work space for the student to use in between group or whole class activities.

Occupational therapists and speech therapists can assist with setting up environments and creating programmes for students with special sensory needs. It is also important to talk to students and their families about what would best support them to learn in a range of physical environments, and to make adjustments accordingly.

Using a range of visual supports

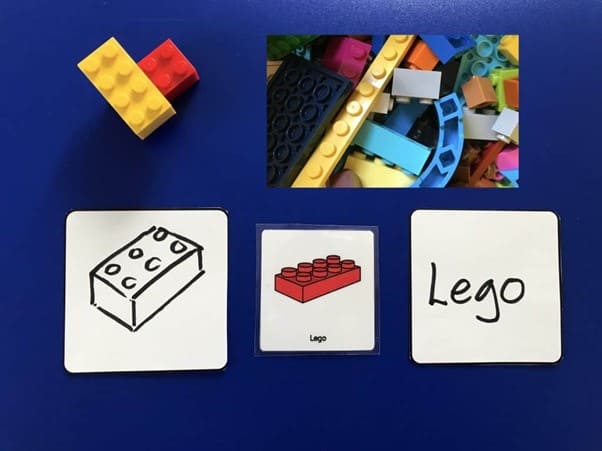

The use of visual supports in the classroom assists autistic individuals to process their day and understand the environment around them. Research suggests that visual supports are particularly effective in developing student communication and understanding, because it draws on their strong perceptual skills and visual memory[5]. Some of the types of visual supports that can be used include objects, photographs, drawings, symbols, and written cues for students who respond well to text (See Image 1).

These kinds of supports can be used to introduce daily schedules and routines, reinforce the meaning of verbal instructions, and to give structure to learning activities. The use of visual supports can increase student engagement, reinforce positive behaviour, provide a foundation for developing student independence and communication skills, and, importantly, allows students to build on their strengths. Visual symbols are most commonly used and are easy to prepare. Laminating the visuals and using velcro or magnets on the back ensures that they will last and can be reused.

Image 1: An example of different kinds of visual supports

Visual scheduling. Visual schedules are cues that let students know what activities are occurring and in what sequence. The ultimate aim of using visual scheduling is to develop student independence in transitioning from activity to activity throughout the day. These are important skills to develop as transitions can be particularly difficult for autistic students. Without the right support in place, transitions can often become times when so-called challenging behaviours occur. In order to develop independence during transitions, the student needs to be taught the steps and sequence involved in following a schedule. Adult modelling and prompting can be used to teach these skills, and then phased out over time as the student’s independence increases.

There are a number of ways to integrate visual scheduling into classroom practice. Visual scheduling can be as simple as showing students the first activity, and then the next activity, or could be schedules by learning block or full day schedules[6]. The type of visual schedule to use, and the most appropriate place to start, should be based on the specific learning needs of the individual.

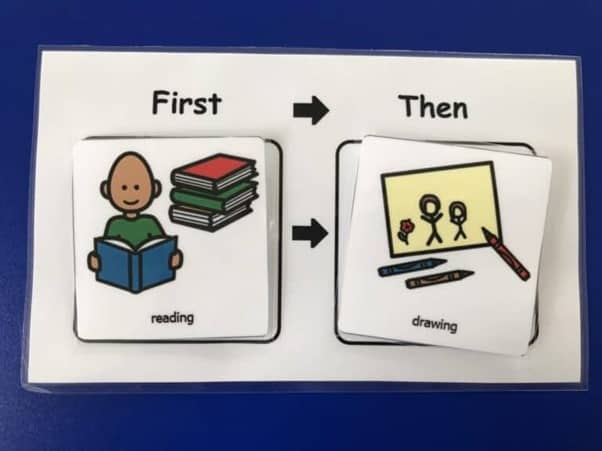

First, then. The first, then strategy is a strategy that lets the student know what first needs to be done in order for them to then be able to participate in an activity or have an item of their choice. When introducing the first, then structure, verbal instructions should be given in a clear voice while pointing to each activity, for example, ‘first reading and then drawing’.

Image 2: Visual cues for a first, then strategy

The then activity or object needs to be something that is preferred and therefore highly motivating for the student. No additional verbal language other than the first, then instruction should be used. This instruction may be repeated alongside the visual first, then cues if needed (see Image 2). It is important to give the student time to process this instruction and to guide them back to the visual cue if necessary. The number of times an instruction needs to be repeated will usually decrease over time as long as the language and delivery of the instruction is consistent.

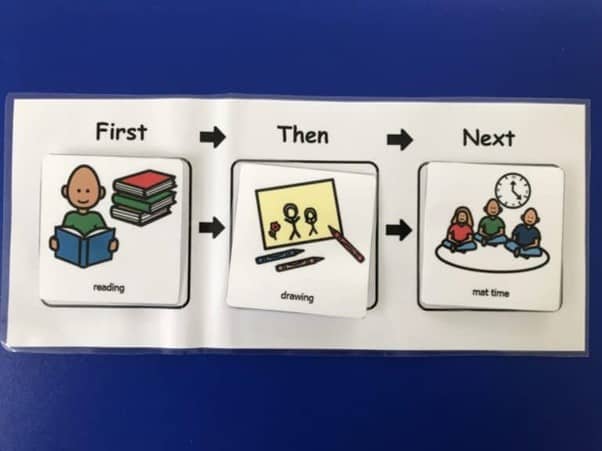

First, then, next. Once the first, then strategy has been mastered, next can be added to the visual cue. Introducing the concept of next teaches the student to anticipate change in events and helps them to transition from their preferred activity to another required activity. Using first, then, next also signals that their time with a preferred activity or object is not permanent. When introducing the first, then, next structure, apply the same principles as for first, then. Clear verbal instructions should be used with the visual cue in the student’s sight (see Image 3). The teacher should point to each activity as it is said, for example, ‘first reading, then drawing, and next mat time’. When the student has transitioned to the then, their preferred activity, visual timers can be used to set a time limit and aid the student’s transition from their preferred activity to the next required one.

Image 3: Visual cues for a first, then, next strategy

Learning block and full day schedules. Visual learning block and full day schedules can be used for students who are able to follow instructions that include multiple steps. Visual schedules typically include the key learning activities in order of their sequence. For some students, tick box visual schedules can be used, with each activity being ticked off as it is completed. For other students, ‘finished’ boxes can be used as a place to put the visual symbol once the activity has finished or is completed (see Image 4).

Image 4: A visual schedule including a ‘finished’ box

There are a number of steps required in being able to follow a visual schedule, such as going to the schedule when needed, taking visual symbols from top to bottom, moving to the area of the classroom that the activity is occurring in, referring back to the schedule when an activity has finished, and placing the visual symbol for the completed activity in the ‘finished’ box before re-checking the schedule.

When introducing a visual schedule for the first time, it is important not to overload the student with too much information. Visual schedules organised for the current learning block (for example, morning block, middle block, after lunch) may be easier for the student to interpret. Once the student has mastered following schedules structured by learning block, an extra block may be added, gradually adding more visuals until the student is able to follow a full day schedule. Visual timers and verbal time warnings (such as 5 minutes, 3 minutes, 1 minute) may also be used to signal to the student when an activity is ending, and when it is time to refer back to their visual schedule.

Structured learning activities. Once a student has transitioned to an activity, the next step is for them to complete the activity. Clearly structured tasks and instructions can support students to understand what they are expected to do. Learning tasks that are clear and structured are especially beneficial in assisting autistic students to organise, sequence, and process the information they need to be able to begin and successfully complete required learning tasks. Visual support can again be used in this situation to break down the steps required to successfully complete the learning activity. For students who are able, written instructions can be used with clearly numbered steps. Colour coding, highlighting key information, individual work trays, easy access to materials or resources, and separating steps of an activity into envelopes or small boxes are other ways that activities can be organised to support student success.

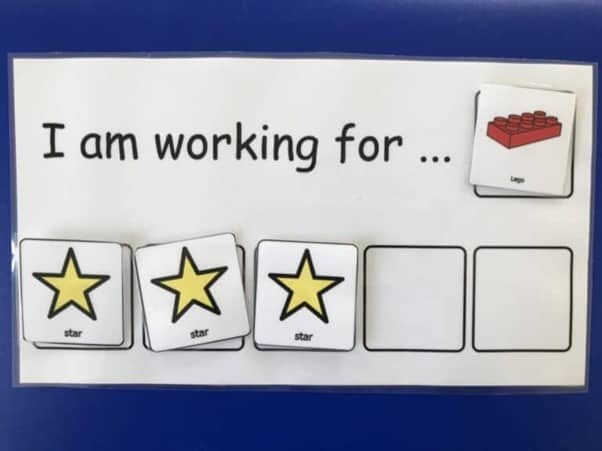

Visual contracts. Visual contracts are a reward system that can be used to motivate students to engage in learning activities or to complete required tasks. Visual contracts rely on the use of a powerful student motivator, like an object or preferred activity for which the student is prepared to work. This motivator or reward is typically something that the student and teacher negotiate together. In order to receive the reward, the student must collect tokens (see Image 5). These tokens can be buttons, stickers, or other small items. Each token represents a portion of the overall task that has been completed. The final token is not awarded until the task is fully complete and the requirements of the visual contract have been fulfilled.

Image 5: A visual contract

Social and emotional needs

Autistic students do not always develop social and emotional skills in the same way as their typically developing peers. They may struggle with peer interaction and communication, understanding appropriate social behaviour, and expressing their needs and emotions rationally, although recent research has found that differences in communication between neurotypes do not exist to the same extent between autistic people[7]. Extra support may need to be provided to students who find it challenging to manage specific social situations. It is also beneficial to help build the skills of all students in processing and regulating their emotions.

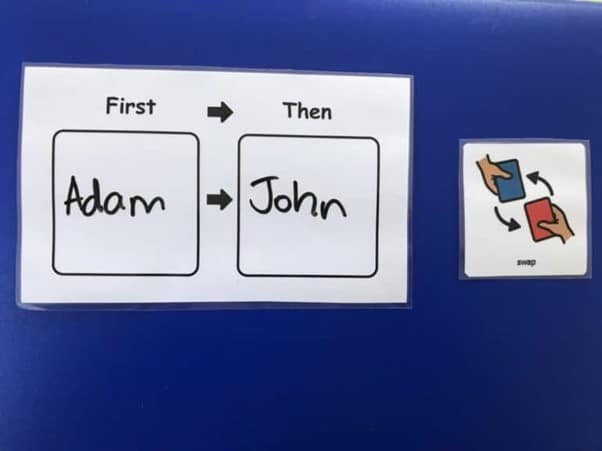

Peer interaction. It is important to educate other students in the class about autism and to promote positive peer interactions so that the autistic student is not socially excluded. The first, then visual cue can be used to support turn-taking during games and activities. For example, ‘first Adam’s turn, then John’s turn’ (see Image 6). Alternatively, a swap visual (see Image 6) may be used to promote sharing and parallel play. In this instance, each student would have an activity or object. When the teacher signalled swap both verbally and by using the visual cue, students would swap activities or objects with a peer.

Image 6: Visual cues for using the first, then strategy and a swap visual to support peer interaction

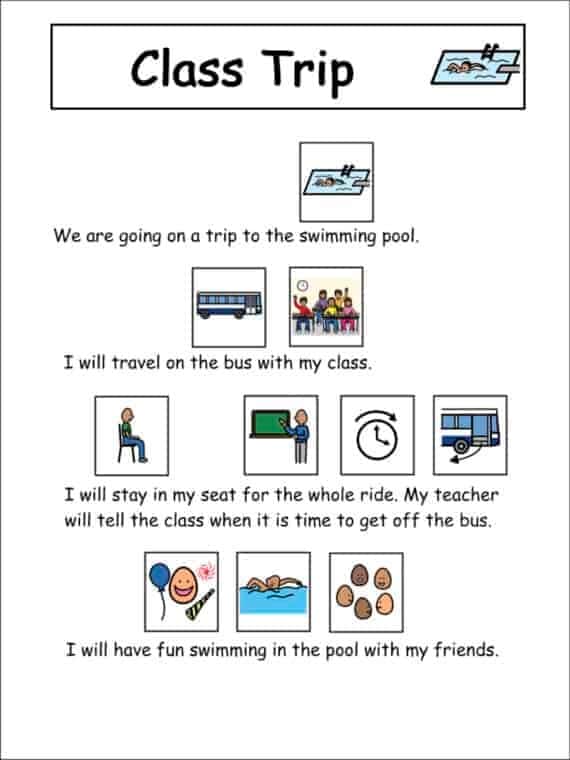

Social stories. Social stories are individualised stories that can be used to support students to develop social skills and to prepare them for social situations. These stories are both concise and specific in detail. They generally include key information about the who, what, when, where, and why in social situations, and use a combination of both visual cues and written text (see Image 7)[8]. Social stories should be designed to suit individual student needs so that students are able to access and interpret the intended message effectively. The main purpose of using social stories is to support students in understanding specific social situations and expected behaviours associated with them.

Image 7:An example of a social story

Endnotes

[1] Kanner, L. (1943). Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child, 2, 217-250.

[2] Autism NZ. (2022). Autism Terminology Guidance From the Autistic Community of Aotearoa New Zealand (autismnz.org.nz)

[3] Heyworth, M. (2021). Introduction to autism, Part 1: What is autism? Reframing autism. https://reframingautism.org.au/what-is-autism/

[4] Mesibov, G. B., & Shea, V. (2010). The TEACCH Program in the era of evidence-based practice. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(5), 570-579.

[5] Frost, L., & Bondy, A. (2002). The picture exchange communication system training manual (2nd ed.). New Castle, DE: Pyramid Educational Consultants Incorporated.

[6] Blome, L., & Zelle, M. (2018). Practical strategies for supporting emotional regulation in students with autism: Enhancing engagement and learning in the classroom. London, England: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

[7] Davis, R., & Crompton, C. (2021). What do new findings about social interaction in autistic adults mean for neurodevelopmental research? Perspectives on Psychological Science. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620958010

[8] Timmins, S. (2017). Successful social stories for school and college students with Autism: growing up with social stories. London, England: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

By Julie Skelling