Creativity has been a part of the human condition ever since we first began to think and ask questions of ourselves and our surroundings. Humanity’s view of creativity has evolved significantly in both eastern and western civilisations. In ancient Rome and China, creativity was said to be a gift bestowed by the gods to a select few. In the nineteenth century, the more romantic view of the creative muse took hold. Until the 1920s, creativity was seen to be a somewhat mystical quality which lay firmly in the realm of the arts and the eccentric.

Fortunately, creativity is now a science. We know that creativity is possible in all fields of human endeavour and that everyone has the capacity to be creative. Furthermore, it is not limited to fields that are more traditionally seen as creative, such as the visual and performing arts. Not only can creativity be taught, learned and assessed, but we also know the factors that make up creativity, as well as the social, environmental and individual qualities that support its development and expression. In the past 20 years, the capacities and competencies of creativity have become important in education around the globe. This importance was perhaps first informally recognised in primary school education, where subjects are often taught in a more integrated fashion than in secondary school. However, education systems have now realised that students need to leave school with not only literacy and numeracy but also digital and creative competencies. Creativity is now a feature, though often explained and explored quite differently, in many international curricula.

Creativity in primary school education: Teaching with creativity

Teachers strive for variation in their pedagogic approach in the classroom. They also strive to model behaviours for the students to adopt. By demonstrating that there are many approaches to teaching a lesson, just as there are many approaches to learning knowledge and skills in a lesson, teachers who teach with creativity in their classroom find that their students are more motivated and engaged. A fairly straightforward example is as follows. The journey from long addition to the rules of multiplication can be difficult for some students to understand. Asking students to discover mathematical rules through constructing objects rather than writing equations is one example of teaching with creativity. Research has found that, if teachers use multimodal ways in presenting key information in mathematics, students not only feel more creative but also more competent in maths.

A pre-requisite for teaching with creativity is a sufficient level of knowledge and skills in a given subject, as research has demonstrated that teachers who lack confidence in a particular subject or unit of work are more likely to teach from pre-prepared resources like textbooks and worksheets and less likely to experiment with a variety of teaching methods. Most primary school teachers are naturally more confident in some subjects than others. Teachers with a bigger toolkit of options to approach a particular unit of work also feel a greater sense of satisfaction and enjoyment in their teaching[i].

Primary school students are very open to exploring ideas and concepts, so teaching with creativity in the primary school classroom can mean using a bank of open-ended questions. For instance, in a science lesson on states of matter, start by asking the students to give examples of things that freeze and things that boil. This can lead to a science experiment, looking at how different objects behave under variations of temperature. Using open-ended questions rather than giving prepared examples helps to identify and activate students’ prior knowledge.

Another example of teaching with creativity in the primary school classroom is demonstrating to students that failure is part of learning. For example, most teachers have had lessons that somehow did not go as planned. Being open about this with your students and inviting them to offer alternative ways of explaining and understanding the concept being taught is an excellent way of modelling the attitudes of creativity. You can also demonstrate to students your creative process. For example, even though you are not an artist, you might show students some drafts of your attempts to draw a cat. Why is one draft better than another? Teaching with creativity is about using the environment, attitudes and processes of creativity in your teaching. It can also mean exposing your creative processes to your students and discussing what it means to be creative.

Introducing creativity to students: Teaching about and for creativity

Creativity is like any other element of schooling: it requires knowledge, skills, application and practice. Experience in schools has shown that short explicit instruction in elements of creativity, integrated into the current classroom subject, is the most effective method of introducing creativity to students. Creativity is not a separate subject, and teaching creativity is more effective if the elements are incorporated throughout the learning process.

Over time, teachers also develop an understanding of what low, medium and high levels of creativity look like in each of the subjects they teach and in the year level they are teaching. At the primary school level, students are working in what researchers of creativity call little-c and mini-c[ii]. Little-c is the very beginning of the creative process – what we might consider everyday creativity. Mini-c is more deliberate and planned creativity. It can be observed in the classroom and reflected in formative observations and assessments where applicable.

When planning lessons, teachers need to think about the physical and social learning environment of the lesson. Does the lesson involve individual work or are students being creative in groups? An important part of creativity is that students feel a sense of psychological safety. This means that they are able to ask questions and explore ideas in an open way, without being shut down or criticised by the teacher or fellow students. Primary school teachers are aware that learning takes time for younger students and the safer they feel to explore their ideas and how they think, the better that learning will be.

The second stage for teachers in their planning is to consider the attitudes and attributes that the students will need to demonstrate in order to be creative. Attitudes such as curiosity and openness to new experiences and attributes such as resilience and risk-taking all help students to be more creative.

Thirdly, it is necessary to consider the method of problem solving and the stages of the problem-solving process. With very young students, it is better to focus on just one small element, such as how many ideas they can generate, or how many ways can they record ideas – do they write them, draw them, or record them on video? Which way works best for them with a particular problem in a subject at a particular time? As they mature, students should have the opportunity to experience a variety of elements of problem solving which eventually come together as a complete process.

The final element to be considered is that of the outcomes – the product or the results – of creativity, although it is not necessary to focus only on the final creative product. Primary school students may be considered successfully creative if they ask a specific number of questions. They may demonstrate curiosity or resilience, or give constructive feedback to a classmate. If students are asked to show certain creative elements in a presentation, feedback can be given on the individual elements as well as the final result. Teachers can give students supportive feedback on all these aspects of creativity. It is also important to remember that all of these micro-components will build over time, enabling students to become more confidently and capably creative.

Examples of teaching for and with creativity in music and STEAM

The following two examples demonstrate some elements of creativity. As you read them, try to look for which elements are being used. You will see how each of these elements may easily and readily transfer to whatever subject you are teaching.

Creativity in primary school music

Some teachers can find teaching music quite daunting. Research has shown that strong negative early experiences in music, such as being asked not to sing in the school choir, can lead to negative self-belief which can have a lasting impact. In the New Zealand Curriculum, music is called ‘sound arts’. The following unit of work, suitable for around the year three level, explores the knowledge and skills of how instruments work. It combines the subjects of music, technology and science, at the same time working on students’ coordination skills. It is important that students can see links between subjects and also the elements of creativity being covered.

You will notice that the instructions below are simple in detail. The essence of creativity is that you as a teacher will personalise this unit of work to suit your own teaching style and the needs of your individual class.

Elements of teaching with creativity:

- Asking open-ended questions such as ‘how do instruments make sound’?

- Demonstrating experimentation

- Demonstrating trial and error

Elements of teaching forcreativity:

- Encouraging an environment of positive feedback

- Encouraging an attitude of curiosity

- The process of trial and error through model-making

- Creating a flute which plays music from a straw

Once you have made straw flutes of different pitches, it is possible to make music. This could also be an introduction to other types of musical instrument that could be made in the classroom, such as strings and percussion.

Creativity in STEAM

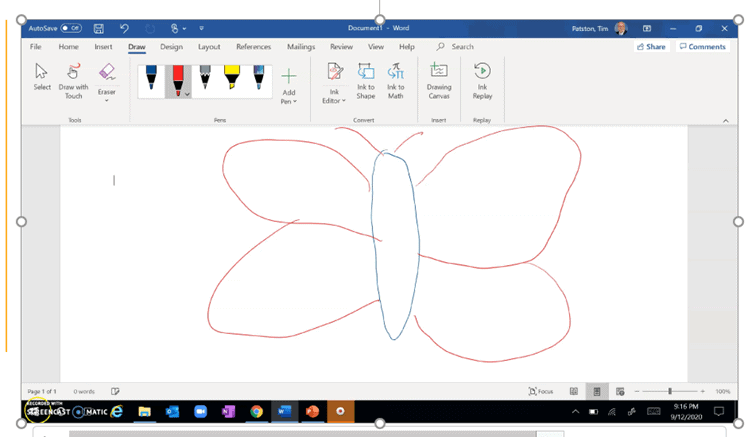

This unit of work, for Year 6, explores science, technology, engineering, arts and maths through the lens of the butterfly. This unit of work begins by asking the students how to draw a butterfly. The picture below was drawn by my Grade 6 daughter.

Elements of teaching with creativity:

- Asking open-ended questions

- What do butterflies look like? (Art – Drawing & Maths – Symmetry)

- What do butterflies eat? (Science – Biology)

- How do butterflies fly? (Engineering)

- How many ways can you make a model of a butterfly which flies? (Technology)

- Encouraging students to share pre-existing knowledge about butterflies

Elements of teaching for creativity:

- A collaborative environment through group work

- The use of pre-existing knowledge (perhaps from a group discussion of what students already know about butterflies)

- The process of recording ideas (for example, post-it notes as a brainstorming tool)

- Exploring how many different types of flying objects the class can make

In both of the above examples, several elements of teaching and learning are at play. Firstly, in both instances the students are developing the knowledge and skills appropriate to the subject which they are studying. Secondly, the teachers are demonstrating that they can teach with creativity by using multimodal methods of instruction. Thirdly, the students are building their creative capacities in the environment, the attitudes, the process and the products of creativity.

References

Collard, P., & Looney, J. (2014). Nurturing creativity in education. European Journal of Education, 49(3), 348-364.

Craft, A. (2001). An analysis of research and literature on creativity in education: Report prepared for the Qualifications and Curriculum Authority.

Runco, M. (2008). Creativity and education. New Horizons in Education, 56(1), 96-104.

Endnotes

[i] Norouzpour, F., & Pourmohammadi, M. (2019). The effect of job satisfaction on teachers’ creativity in using supplementary equipment in learning English in Iranian English institutes. European Journal of Education Studies, 6(4), 267–275.

[ii] Kaufman, J. C., & Beghetto, R. A. (2009). Beyond big and little: The Four C Model of creativity. Review of General Psychology, 13(1), 1-12.

By Tim Patston