Teachers’ expectations of their students’ learning may be more important in influencing student progress than pupils’ abilities. ‘High expectation teachers’ believe that students will learn faster and will improve their level of achievement. They also have more positive attitudes towards learners and more effective teaching practices. This paper outlines the key differences in teaching practices between low expectation and high expectation teachers. It provides helpful, practical teaching strategies to move towards high expectation and better teaching.

Why high expectations are important

Teachers’ beliefs about their students and what they can achieve have a substantial impact on students’ learning and progress. Research shows that as well as expectations about individual students, teachers can be identified as having uniformly high or low expectations of an entire class of students. High expectation teachers believe that students will make accelerated, rather than normal, progress, and that pupils will move above their current level of performance (for example, from average to above average). Whereas, in general, low expectation teachers do not expect their students to make significant changes to their level of achievement over a year’s tuition. Studies show the effects of teacher expectations are pervasive. It seems it is not students’ ability that determines achievement, but rather their teachers’ expectations, and associated attitudes and practices. This is great news for teachers – you can make a difference.

Christine Rubie-Davies at the University of Auckland has investigated teacher expectations in New Zealand classrooms. Her research shows that teachers’ different levels of expectations lead to different instructional practices. For example, teachers with low expectations for students’ achievement may present less cognitively demanding experiences, spend more time reinforcing and repeating information, accept a lower standard of work, and emphasise rules and procedures. Low expectations set up a chain of low-level activities and, therefore, lower learning opportunities. When teachers’ expectations increase, their attitudes, beliefs, and teaching practices change. In general, high expectation teachers employ more effective teaching practices. When students are given more advanced opportunities to learn, they can make more progress.

The students of high expectation teachers show larger achievement gains, while the students of low expectation teachers make smaller or negative gains. The positive attitudes and equitable teaching practices of high expectation teachers also lead to higher levels of engagement, motivation and self-efficacy in students.

Research also shows that students are very aware of their teachers’ expectations for them. Students can provide examples that demonstrate a very subtle understanding of teacher attitudes, conveyed through words, tone and non-verbal communication. Students of teachers with low expectations come to view themselves more negatively, while students with high expectation teachers develop or maintain positive attitudes across the year, even when they have only made average progress. Positive attitudes to learning and about themselves as capable learners contribute to students’ greater achievement with high expectation teachers.

Key differences between high and low expectation teachers

Teachers’ expectations for students lead them to deliver instruction in line with these expectations. For example, when teachers believe that low-achieving students are not capable of higher-level thinking, they provide differentiated learning experiences in their classes. Key areas of contrast between teachers with high expectations and teachers with low expectations include the quality of teaching statements, feedback, questioning and behaviour management.

| Low expectation teachers | High expectation teachers |

| Constantly remind students of procedures and routines. | Have procedures in place that students manage themselves. |

| Make more procedural and directional statements focused on students’ activities and behaviours, rather than on learning. For example, “Here is your reading book and worksheet for today. Off you go and read it and then do your worksheet.” | Make more statements focusing students’ attention on learning, or teaching new concepts, or relating current learning to prior activities and knowledge, or explaining and exploring concepts with students. For example, “This story is called … With that title, what do you think it is going to be about?” |

| Communicate details of the activities students have to complete. | Communicate learning intentions and success criteria with the class. |

| Ask predominantly closed questions based on facts. For example, “What’s the formula for finding area?” | Ask more open questions, designed to extend or enhance students’ thinking by requiring them to think more deeply. For example “And why do you say that? What clues in the story made you think that?” |

| Manage behaviour negatively and reactively. | Manage behaviour positively and proactively. |

| Make more negative statements about learning and behaviour. | Make more positive statements and create a positive class climate. |

| Set global goals for learning as a frame for planning teaching. | Set specific goals with students that are regularly reviewed and used for teaching and learning. |

| Take a directive role in planning the sequence of instruction and activities, and provide little opportunity for student choice. | Take a facilitative role and support students to make choices about their learning. |

| Link achievement to ability. | Link achievement to motivation, effort, and goal setting. |

| Use ability groupings and design different learning activities for each achievement group. | Encourage students to work with a variety of peers for positive peer modelling. |

| Provide lots of repetition in lower-level activities for low-ability children, and advanced activities for high-ability learners. | Provide less differentiation and allow all learners to engage in advanced activities. |

| Break learning down into incremental steps and organise learning in a linear fashion. | Undertake more assessment and monitoring so that students’ learning strategies can be adjusted when necessary. |

| Spend more time with low-achievers and give high achievers time to work independently. | Work with all students equally. |

| Give praise (or criticism) focused on accuracy. For example, “Well done. That’s right.” | Give specific, instructional feedback about students’ achievement in relation to learning goals. For example, “Nice addition, I like the way you have kept your numbers in straight columns so you didn’t get the tens and hundreds muddled.” |

| Respond to incorrect answers by telling student they are wrong and asking another student to respond. | Respond to incorrect answers by exploring the wrong answer, rephrasing explanations, or scaffolding the student to the correct answer. |

| Use incentives and rewards for motivation. | Base learning opportunities around students’ interests for motivation. |

What your teaching practices say about your expectations

Your teaching practices indicate your expectations of students. What do your practices reflect about your beliefs about your students and their ability to learn?

You ask open questions: Your students are encouraged to give their own ideas more often. You believe your students have good ideas to offer: high expectations.

You praise correct answers: You focus on performance, rather than the effort that goes into learning. Your students become performance-oriented (if they are high achievers) or develop performance-avoidance strategies if they have difficulties with the content, with negative consequences for motivation and engagement. Students are not supported to understand how they can improve: low expectations.

You do lots of formative assessment and your feedback develops learning: Your feedback is instructional with information about achievement and the next steps for learning, so that the student is enabled to make better learning decisions. For example, you might give a student a range of possible next steps, and say, “We could work on this or we could work on that, what would you like to work on?” Students are empowered and motivated to make progress in their learning, at exactly the moment that they are ready: high expectations.

You rephrase questions when answers are incorrect so that students are enabled to be successful, and to guide strategies for success: high expectations.

You use ability groupings to match instruction and activities to students’ differing learning needs: Your students are aware of differentiation and it has an effect on their motivation and their self-perceptions of achievement. Students have less freedom to make individual progress as they are constrained by the activities set for them: low expectations.

You extend high-achieving students with advanced activities and applications of skills and knowledge: Your students are aware of differentiation and it has an effect on their motivation and self-perceptions of achievement. It appears to the class that some students have more privilege or teacher esteem, because high achievers are trusted with some autonomy but low achievers are constrained to highly regulated teacher-set activities: low expectations.

You support low achievers by using a slower instructional pace, lots of repetition and review of prior learning. Low achievers’ progress is confined to the pace at which their learning is presented to them: low expectations.

You provide a range of learning activities and give students choice because you believe that if low achievers can become more motivated and engaged, their achievement will increase. You believe lack of achievement is due to a lack of motivation and effort, and not constrained by a lack of ability: high expectations.

You provide a clear framework for learning in terms of learning intentions and success criteria, so that students are cognitively and behaviourally engaged and can be trusted to manage their own learning: high expectations.

You set individual goals with students that are specific, regularly revisited and revised as students make progress. Student learning progresses at the individual student’s pace, rather than being constrained to a carefully planned progression implemented by the teacher, remaining focused on mastering one learning outcome until the entire group has achieved it. Individual learning goals help students get engaged in learning and intrinsically motivated, and help develop students’ independence: high expectations.

How to adopt teaching practices of high expectation teachers

High expectations on their own are not enough to impact on achievement. It is the combination of high expectations with particular beliefs and teaching practices that have the biggest impact on student learning. In fact, the practices of high expectation teachers are those of well researched effective teaching practice.

Christine Rubie-Davies at the University of Auckland has demonstrated that when teachers adopt practices common to high expectation teachers (specifically relating to grouping and activities, class climate, and goal setting), there are gains to students’ achievement.

Here are some of these high expectation practices that will make the biggest difference to achievement.

Class climate

- Create a warm, supportive classroom climate. Promote peer co-operation and collaboration. Do something as a class each day to build class cohesion. Use buddies, inter-group games and circle time, and promote kindness through games and activities. Look at positive psychology resources for ways of increasing positive emotions in your class. The more positive the relationships in your classroom are, the more emotional support is available to students.

- Show trust by giving students responsibility for their learning, while showing interest in what they are achieving. Develop positive regard for each of your students. Research shows that students can tell when teachers’ displays of warmth and emotional support are not genuine, and that students resent teachers that provide differing levels of emotional support to individual students. Interestingly, while teachers believe they are providing more emotional support to their low-achieving students, students perceive the opposite.

- Take time to enjoy and get to know your students and their interests. Getting to know your students at a personal level and valuing student diversity can have strong effects on class tone. Create authentic relationships with students, since the relationships students develop with their teachers are important for their academic and social progress. Teacher-student relationships have a marked effect on achievement, and influence peer relationships.

- Incorporate student interests into activities to ensure high levels of motivation and engagement. Students enjoy school when they are able to choose their own activities, when activities are focused on their interests and are accompanied with clear goals and clear feedback.

- Establish routines and procedures at the beginning of the school year and give ownership of responding to such routines to the students, so that reminders are unnecessary, and most classroom talk can focus on learning.

Goal setting

- Communicate the learning goals for the class clearly, as this facilitates students’ goal setting. Goal setting is more likely to be effective in classrooms where students understand what they are learning and how they can show they have been successful. For example, use the acronym WALT (“We are learning to … ”) at the beginning of every lesson, or after introductory or motivational activities. Ask children to generate the success criteria with you, for example, “We have used at least four describing words in our story about our visit to the farm”, or “We can tell someone the names of eight planets in our solar system”. Prominently display both learning goals and success criteria. Occasionally provide students with the big picture about the reasons for learning goals, for example, “Learning to include describing words in our stories makes our stories more interesting, and readers are much more likely to enjoy our stories if they are interesting.” This helps all students engage.

- Have students set their own goals and work towards achieving these, with you as their facilitator and guide. Students can then move forward in their learning at their own pace (rather than having to spend an allocated number of lessons, or a set number of pages in a workbook, on a skill), and this enables rapid progress. Allow an hour a month in class for goal setting (one month is a good timeframe for primary students, although very young students might require weekly goals). Support students to learn to set appropriate goals at first, using conferencing, for example.

- Teach students about SMART (specific, measurable, attainable, results-oriented, and time-bound) goals. Students’ commitment to goals is supported when goals are specific, clear, and challenging but achievable. An appropriate level of challenge is particularly important, as the satisfaction and sense of accomplishment of attaining a challenging goal increases student self-efficacy and motivation. Have students write goals down or share them with peers; these are powerful motivators to completing the goals, and keep goals clearly visible.

Examples of SMART goals for primary students:

- By the end of this month I will be able to add and subtract two-digit numbers accurately at least 90% of the time (I need to get 9 out of 10 correct).

- By the end of this month I will choose 20 words in my reading books that I don’t know at the moment and will find out what they mean.

- By the end of this month I will make my writing more interesting by using describing words in all of my stories.

- Promote self-directed learning by breaking larger goals into proximal goals, which detail the specific steps needed to reach the challenging goal. Proximal goals enhance motivation because progress towards proximal goals informs students that they can be successful and enhances their feelings of self-efficacy.

- Focus on mastery goals (emphasising the process of learning, self-improvement and new skills acquisition) over performance goals (based on an outcome or the ability to demonstrate competence). Performance goals imply winners and losers, success and failure, whereas all students can achieve skill-based goals at their level. Mastery goals are emphasised when students are required to give more than one-word or factual answers to questions, when they are asked to read or engage with complex texts or problems, and when students collaborate. All of these activities downplay notions of ‘getting it right’ as the goal of learning. Mastery goals are associated with better motivation, engagement, and achievement, and most positively related to learning and effective outcomes, such as deeper thinking, more systematic processing of information, and greater effort and persistence. While mastery goals and performance goals can be synergistic (with students motivated to both learn and achieve), for lower-achieving students, focusing on mastery goals maintains higher levels of motivation and interest.

- Use portfolios, goal-setting, self-evaluation, self-reflection and peer feedback which increase both students’ self-efficacy and their achievement. When students have high levels of self-efficacy, they choose more difficult goals and show greater commitment to their goals. They are more resilient to setback and failure, increasing their effort to achieve the goal.

- Use carefully targeted feedback to assist students with goal setting and reaching goals. Feedback should always follow on from instruction and should be based on students’ current understanding or stage of skill development, otherwise students may not be able to make the adjustments needed in their learning to achieve their goal. Feedback helps reduce frustration and risk of failure, and supports students’ engagement with the goal by directing them to appropriate actions. Students come to understand that if they fail or make mistakes, they will be supported by sensitive feedback and guidance on how to overcome errors, which helps them to maintain motivation. Students generally find process-oriented feedback more useful than competence-oriented feedback.

Grouping

- Group children flexibly in small (4–6 students) heterogeneous groups comprising a range of abilities and genders. Average and low achievers have been found to benefit when they work with a range of peers across the class. Be strategic about group formation, promoting social relationships and social support by ensuring that all students work with each other at some time over the year. Regular reshuffling of groups enables students to develop better friendships across the classroom, which leads to higher levels of peer support and a more positive class climate.

- Change groupings fairly frequently, at least once a month and sometimes weekly, using individual cards for each student’s name to display groupings easily. Some high expectation teachers group children by ability for instruction, but not for learning activities. Flexible grouping arrangements mean that students receive instruction at their current level of need without experiencing the strict stratification of ability grouping and its negative effects on self-esteem and motivation. Some high expectation teachers do not group students even for instruction, but just draw students together to teach them a skill when they need to learn it, or work with students individually.

Ideas for assigning groups

Shuffle name cards for random groupings, or agree groups at the beginning of the year based on students’ favourite colours or authors, their pets or other criteria such as alphabetical name order, birth month or shoe size. Create a clock spinner which can be used to randomly select which groupings will be used for that lesson’s activities.

- Structure your classroom so that differentiation between high and low achievers and the kinds of learning experiences they engage in are minimised. All activities should be available for all students and there should be a variety of levels of attainment possible within each activity. Students can choose something at their level or perhaps something more challenging while working with a peer. Teachers report that children are likely to select an activity that suits their level of skill. For example, students rarely choose to read books that are too easy (because they become bored), or too hard (because they become frustrated).

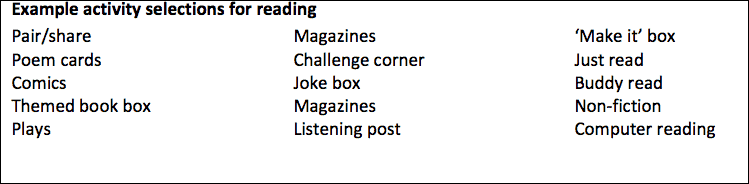

- Allow students to choose their own activities from a range of options so that they experience some autonomy and responsibility for their own learning. Student choice creates a warmer and more supportive classroom climate, but initially students will need instruction on how to do each independent activity. Then you might offer a range of activities and direct students to complete a certain number. You might make a list of daily reading activities for example, and mark with a peg which ones students can choose from for this lesson. Or you might create a ‘tic tac toe’ 3×3 grid in which students must select three activities either across, down or diagonally. Have students change activities regularly — at which point you can also work with a different student or group for your planned teaching activities.

Rethinking pedagogical beliefs

Here are some aspects of your classroom teaching you might like to reflect upon in order to transform your expectations.

- Reflect on who currently holds control of learning in your classroom. Control and student choice are identified as key aspects contributing to student learning outcomes. Are your expectations of students leading you to control and manage learning on their behalf? Could you entrust more of the decision making around learning to students, thereby showing students your greater expectations for their involvement and contribution?

- Investigate student relationships using a sociogram or questionnaire. Ask students to nominate three students they would like in their group. You will be able to analyse the breadth of relationships across the class, and then make plans to improve student relationships through different groupings, for example. Be careful of harming existing relationships through student gossip about nominations, however. Emphasise the confidentially of the information they provide, don’t allow student discussion of their choices, and explain the information is only used for grouping purposes.

- Investigate your questioning. Check who is being asked questions and how you respond to students’ answers. Check that all students are being asked challenging, open-ended questions that require them to think at deeper level, and that such questions are not being reserved only for higher-achieving students.

- Reconsider ability grouping in favour of mixed ability grouping. Heterogeneous grouping and challenging activities for all students provide more equitable opportunities to learn. Research demonstrates that low-achieving students are able to narrow the achievement gap when they are provided with challenging instruction in a warm and supportive class environment. Studies show few positive benefits for ability grouping. When teachers differentiate, they tend to form low expectations for students in the lower groups, and potentially limit their learning activity to review and repetition within a slower and heavily structured instructional pace. Differentiation is also associated with negative effects on self-esteem for both high and low achievers, and is likely to undermine teachers’ relationships with all students as students tend to perceive that higher achievers are valued more by the teacher. Instead a more flexible grouping arrangement (arranging a group of students to work with the teacher on a specific skill as the need arises) is better able to provide instruction for students at the appropriate skill level.

Is it time to examine your pedagogical beliefs, reset your expectations, and challenge yourself by implementing new teaching practices that will better serve all your students?

High expectations self-assessment checklist

How often do you use the following high expectation practices in your teaching?

| Rarely | Sometimes | Regularly | |

| Ask open questions | |||

| Praise effort rather than correct answers | |||

| Use regular formative assessment | |||

| Rephrase questions when answers are incorrect | |||

| Use mixed-ability groupings | |||

| Change groupings regularly | |||

| Encourage students to work with a range of their peers | |||

| Provide a range of activities | |||

| Allow students to choose their own activities from a range of options | |||

| Make explicit learning intentions and success criteria | |||

| Allow students to contribute to success criteria | |||

| Give students responsibility for their learning | |||

| Get to know each student personally | |||

| Incorporate students’ interests into activities | |||

| Establish routines and procedures at the beginning of the school year | |||

| Work with students to set individual goals | |||

| Teach students about SMART goals | |||

| Regularly review goals with students | |||

| Link achievement to motivation, effort and goal setting | |||

| Minimise differentiation in activities between high and low achievers | |||

| Allow all learners to engage in advanced activities | |||

| Give specific, instructional feedback about students’ achievement in relation to learning goals | |||

| Take a facilitative role and support students to make choices about their learning | |||

| Manage behaviour positively and proactively | |||

| Work with all students equally |

Rubie-Davies, C. (2008). Expecting success: Teacher beliefs and practices that enhance student outcomes. Saarbrücken: Verlog Dr. Muller.

Rubie-Davies, C. (2014). Becoming a high expectation teacher: Raising the bar. Hoboken: Routledge.

By Dr Vicki Hargraves